(3/2016) The news has recently broken a story about a drinking water contamination crisis in Flint, Michigan, affecting some 100,000 residents. The villain in the water supply is lead. There is no safe level of lead exposure, and lead poisoning leads to brain damage and behavioral disorders, especially when exposure is to children. The cause in this case is that the city

switched its water supply in 2014 from Lake Huron to the Flint River to save money, sending the water through lead pipes. The change was deemed temporary, but it took longer to develop the new supply line than planned. Due to the composition of the Flint River water, lead was leached from the pipes into the water. Though lead passes through the body fairly quickly, lifetime

damage can be done, especially to small children. Lead only stays in the body for about 30 days, but it’s physical consequences may not be obvious for 3-5 years, but it can cause lifelong damage to the brain in that time.

The switch was supposed to be temporary while a new supply line was built from Lake Huron. The water, according to federal law, should have been tested. When it was finally tested, it was found to contain 19 times more lead than the Lake Huron water. The realization of this problem came when a local pediatrician sounded the alarm after she noted the symptoms of lead

poisoning in a number of local children less than six years of age. On January 16, President Obama signed an emergency declaration for Flint that allows federal aid for items including water, filters, and cartridges for 90 days as well as for other direct federal funding. This story evokes the memory of our earlier story about PCBs in the Hudson River, and the places along

the Hudson that drew their drinking water, especially Poughkeepsie, New York, from the Hudson River. Recently, high levels of PCBs have been detected in the fat of ocean species even though PCBs have been banned for many years.

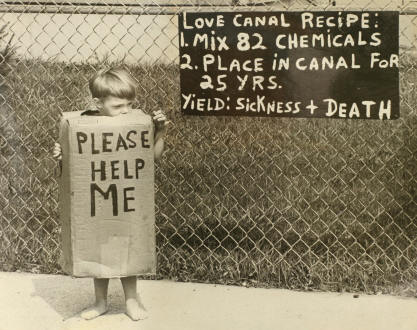

This story recalls an older story from the 1970’s – The Love Canal Pollution Crisis. Love Canal is an aborted canal project branching off the Niagara River, four miles south of Niagara Falls, NY. Adjacent to the canal was a fifteen-acre working-class neighborhood of

about 800 single family homes. From 1942-1953, the Hooker Chemical Company used the partially dug canal as a chemical waste dump. Does this seem shocking? Well, the process had government sanction!

This story recalls an older story from the 1970’s – The Love Canal Pollution Crisis. Love Canal is an aborted canal project branching off the Niagara River, four miles south of Niagara Falls, NY. Adjacent to the canal was a fifteen-acre working-class neighborhood of

about 800 single family homes. From 1942-1953, the Hooker Chemical Company used the partially dug canal as a chemical waste dump. Does this seem shocking? Well, the process had government sanction!

When the period ended, some 21,000 tons of chemical waste had been discharged into the canal, including twelve known cancer-causing chemicals. At the end of this period, Hooker capped 16 acres in clay and sold the land for $1 to the Niagara Falls School Board.

Things were quiet until the late 1970s when it became evident that the neighborhood had an abnormally high rate of illnesses, such as epilepsy, asthma, migraines, and nephrosis, as well as abnormally high rates of miscarriages and birth defects. Several consecutive wet winters in the late 1970s had raised the water table and caused the toxic chemicals to enter into the

basements and yards of local residents and into the playground of an elementary school built directly over the canal.

When these facts became known, activists, most of them working-class women from the neighborhood, began raising their concerns, but were largely ignored by New York State officials. In 1978 President Jimmy Carter declared a state of emergency, and the federal government relocated some 239 families from the area. The controversy continued because another 700 families were

denied relocation, even though testing showed that toxic substances were leaching into their homes. President Carter declared a second state of emergency in 1981, and the remaining families were relocated at a cost of $17 million.

A positive result is that Love Canal and other such incidents alerted the American public and the government to the need for more control over environmental abuse, and new legislation was passed at state and federal levels as the level of consciousness was raised. Such legislation included the 1980 Comprehensive Environmental Response, Composition, and Liability Act (CERCLA),

also known as The Superfund Act. Hooker Chemical had become a subsidiary of Occidental Petroleum. Because CERCLA contained a retroactive liability provision, Occidental was held liable for cleanup of the waste, even though they had not broken any current laws. Occidental was sued by the Environmental Protection Agency, and in 1995 agreed to pay $129 million in restitution.

Many resident lawsuits were also settled as a result of the act. This event and others like it fueled environmental activism across the country. Love Canal was not an isolated case. Many other chemical dumpsites had been created.

Events such as these had a major impact on my consciousness, and then on my career direction and my community activities. I went to Bard College with my family to Dutchess County, NY, on the Hudson River between Poughkeepsie and Albany in 1965 as a chemistry professor, but my professional interests also evolved into environmental science, environmental management, and

environmental activism. I saw it as part of my professional duty to be a responsible community member and not a reactionary activist. In addition to teaching environmental issues, I served on and chaired the Dutchess County Environmental Council, served on a number of regional citizen’s advisory groups, and studied water quality in the stream that passed through the campus

and flowed into the Hudson River. We drew college drinking water from this stream, and we discharged the college’s treated waste into it. I wrote on environmental issues for two local newspapers much like the Emmitsburg News-Journal.

To close, let’s have some good news. In late December the Senate passed the Microbead-Free Waters Act, banning in the future the use of the tiny plastic beads in beauty products that can pollute waterways and endanger marine life. The House of Representatives had already passed a similar bill, and President Obama signed the reconciled bill into law as the Microbead-Free

Water Act of 2015. Microbeads are tiny plastic spheres used as exfoliants in face wash, toothpaste, deodorant and other beauty products. Our wastewater treatment plants cannot handle these tiny beads, and hence they are passed on into our waters. Researchers have found that as many as 8 trillion microbeads find their way into the environment in the United States in a single

day! And that’s only 1 percent of the total microbeads discharged each day. The other 99 percent end up in sewage plant sludge, which is often used in fertilizer on farms. Since microbeads do not biodegrade, they end up in streams and oceans…and in aquatic animals’ stomachs. Manufacturers have until 2017 to fully eliminate them from their products.