Michael Rosenthal

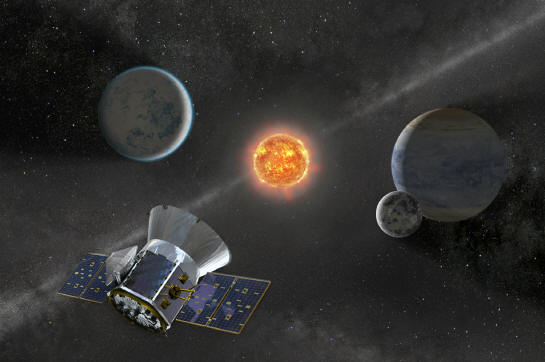

(5/2018) Here are some additional interesting developments in space science. NASA is launching a new spacecraft known as TESS, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite which is intended to take up a lengthy residence of at least two years, between the moon and Earth, scanning the sky for alien worlds. Questions to be addressed include: Are we alone in

the Universe? Are there other Earth-like planets? Is there even microbe life in the galaxy?

It was as recent as 1995 that astronomers discovered a planet outside our solar system – a planet circling the sunlike star 51 Pegasi. In 2009 NASA’s Kepler spacecraft discovered some 4,000 possible planets in a small patch of the Milky Way near the constellation Cygnus. The Kepler is running out of fuel, so it’s time to enter a new phase of

exploration. Astronomers now speculate that there could be billions of potentially habitable planets in our galaxy, as close as 10-15 light years from Earth. The hope of TESS scientists is that we might find a planet close enough to view by telescope…or even visit with an interstellar robot.

The leader of the TESS team is Dr. George Ricker, a researcher at MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research. He expects to find 500 or so Earth-size planets within 300 light-years of Earth. If this is the case, can we really expect that we are the only inhabited planet?

The scale is hard to imagine. Dr. Ricker sys that there are some 20 million stars to look at. Most of the exoplanets will be orbiting stars called red dwarfs, stars smaller and cooler than our Sun. This fact has implications, of course, for planetary life.

Of this enormous number of new planets, as many, they speculate, as 20,000, the plan is to come up with the masses and orbits of some 50 that are less than four times the size of Earth. The exploration team plans 80 nights of searching a year for five years on a spectrograph called Harps North (High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher). It resides

on an Italian telescope in the Canary Islands, a Spanish possession off the coast of Africa.

Harps can measure the mass of a planet and help distinguish its composition and structure. The budget for TESS is $200 million, considered small by NASA compared to other projects.

So what does the spacecraft look like? Does it resemble spacecraft in science fiction movies? It is reported that it is the size of bulky, oddly-shaped refrigerator. The spacecraft will ascend on SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, from Elon Musk’s rocket company about whom we have written previously. On top of the spacecraft will be four small cameras, each with

a 24 degree field of vision. The cameras will spend some 27 days at a time in a spot, and then move on. During the first year, the entire southern hemisphere will be scrutinized. In the second year, the plan is to view the northern sky.

The scale of this study is amazing. Dr. Ricker and his colleagues are working with a list of some 200,000 stars! For life as we know it, a planet must have temperatures that allow liquid water, and there must be enough stability with their sun not to destroy potential life with violent solar flares, which rain radiation lethal to life.

Here’s another astronomy development. Astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope have found the farthest star ever observed from Earth. The star is 9 billion light years away from earth. This observation came about from the fortuitous alignment of a massive galactic cluster. The cluster warped the starlight, bending it to Earth and magnifying the

starlight some 2000 times. Astronomers call the star Icarus, and it is a hundredfold more distant than any other lone star detected previously. This study has been undertaken by Dr. Patrick L. Kelly, an astrophysicist at the University of Minnesota. The discovery was a fortuitous event, discovered while the team was studying Hubble images of a supernova, and the star appeared

as a "blip". The fact that this blip remained stable led the scientists to define it as a stable star, and not a supernova explosion. Another reality of such studies is the realization that Icarus no longer exists! In the time it took for its light to reach earth, it lived out its life. Blue supergiant stars do not have life spans of 9 billion years, and in the time it took

for its light to reach us, its lifetime expired. The universe is 13.8 billion years old, so to view Icarus’s starlight is to look back to three quarters of the age of the universe.

Writing about this topic and thinking about my recent experience with the Mother Seton STEM Fair, stimulates my thinking about the broad range of what we identify as STEM – Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics, and how different from one another careers in the various components can be. There are many choices to be made. One can choose to

work in a laboratory, such as I did as a "bench chemist" in graduate school. One can choose medical science and apply scientific principles to treating patients in need of healing from a wide variety of conditions. One can be a mathematician, and use no more than a computer (or pencil and paper!) to solve problems. One can use the ultimate applied techniques of engineering to

do a wide variety of things, Chemical, Mechanical, Nuclear, and Biological to name a few. These choices represent only a few of the many scientific career options.

I was a successful science student from First Grade on (I skipped kindergarten!). I liked biology from its aesthetic impact – flowers, animals, the outdoors, and more, but I found it too descriptive as a profession for me. I found physics very important, but too mathematical and often too abstract for me. But from Day 1 at it, I fell in love with

chemistry, and made it my career goal in my senior year of high school with my inspiring teacher, Mr. Gillespie. It is so important to find your way into the direction that your skills and your interests coincide, and that was so evident to me in the wonderful science guidance that the students are receiving daily at Mother Seton School. I worry that those of them who head

next to public school will not all receive the personal support that they received at Mother Seton, and I hope that the love of science they are developing will have the necessary momentum to bring them to college with their scientific ambition intact.

Of course, science study at college has its challenges as well. I spent 50 years or so teaching chemistry at small colleges. After my graduate education at a large public university, and watching undergraduate chemistry students in classes of as many as 100 or more students, I became convinced that the best undergraduate college education is in

colleges with small classes and with dedicated teachers. Science is not easy, even for the talented, and mentorship is so important. There is no such thing, in my mind, as "A stupid question," but the classroom structure needs to be such that questions can be asked at the moment of curiosity without the student feeling he or she intruded in the presentation. My greatest

satisfaction was teaching first year chemistry, helping students develop the momentum that could carry them through to STEM careers or related applied professions, such as medicine, dentistry, veterinary medicine, and other health professions.

Michael is former chemistry professor at Mount. St. Marys

Read other articles by Michael Rosenthal