Global warming is changing the flow of ocean currents

Boyce Rensberger

(5/2023) As all observations show, global warming is happening faster at the poles than it is in our temperate latitudes. While the average annual temperature in our part of the Earth has risen by 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit since 1980 (yes, that’s enough to contribute to the weather chaos we’re seeing), the Arctic has had an increase of about 5.4 degrees during the same time.

If you want to see what global warming can do, ask the Alaskan natives whose seaside homes are sinking into the melting permafrost; they are having to move miles inland. Ask the people who race their sled dogs in Alaska’s 1,000-mile Iditarod. There have been recent years with no snow; once-frozen lakes must now be bypassed.

Much the same thing is happening in Antarctica. There are places where the snow is gone, and grass and wildflowers are now established.

Even though we’re not seeing such dramatic changes in Maryland, we eventually might. The cause could be the possible collapse of deep-ocean currents that flow all over the planet.

First a little background:

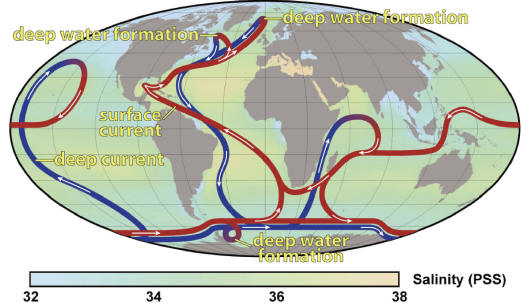

Most of Earth is, of course, covered by water, 70 percent of it. And that water doesn’t just sit there, stagnant. It’s laced with currents—massive rivers of water that flow within the oceans from one part of the globe to another. In our region, we’re most familiar with the Gulf Stream, discovered long ago by Benjamin Franklin. Warm water from the Gulf of Mexico flows along the surface between Florida and Cuba and then up along our East Coast at speeds between four and six miles per hour. The volume of water that flows is greater than that of all the world’s rivers combined.

This oceanic river even has a tributary. Warm water from the Caribbean joins the flow a few miles off the Florida-Georgia state line. The current roughly follows the continental shelf northward and, a few hundred miles off the coast of New England, it turns eastward, bringing warm water to Britain and northern Europe. It’s the reason that palm trees can grow in Scotland, and England, even though these countries are at the latitude of Hudson Bay.

As the Gulf Stream gives up its heat to the northern atmosphere, the water obviously becomes colder. But this is just one of two phenomena that make this water sink toward the bottom of the ocean. One is that cold water is more dense than warm water. Its molecules are closer together. The other phenomenon is that when the surface current reaches far enough north to freeze, it becomes saltier and this makes it still more dense. This happens because when salt water freezes, the water molecules crystalize in a way that pushes away most of the minerals that made the water salty. So, sea ice is basically fresh-water ice. The excluded salt atoms remain in the unfrozen water, making it still more dense.

This doubly dense water sinks, slowly diving into the depths of the North Atlantic and flowing southward. As this deep, cold current moves toward the equatorial region, it picks up heat and, now less dense, rises back to the surface to repeat the cycle. It may help to think of the current as a conveyor belt. The water that is cooling and sinking, "pulls" the warmer surface water behind it. My explanation here is an oversimplification but it helps me get a mental grasp of the phenomena.

Similar currents flow in all the world’s oceans. The scientific picture of all this emerged in the 1980s from the work of the late Wally Broecker, a scientist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. Broecker also foresaw a rise in global temperatures and coined the term "global warming."

He warned that as the Arctic warms, less sea ice will form. As a result, Gulf Stream salinity would not increase as much and, therefore, its water might not become dense enough to sink as fast. This great conveyor belt—and one that does the same thing in the Pacific—could slow down. Global warming, in other words, could slow the Gulf Stream, causing northern Europe to become cooler. That’s one of the counter-intuitive results of global warming. The global average temperature is not uniform across the globe.

Antarctica is warming almost as fast as the Arctic, but the latest report from the UN’s IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) says that its deep-water circulation appears to be slowing twice as fast as that in the North Atlantic.

"[It’s] stunning to see that happen so quickly," said Alan Mix, a climatologist at Oregon State University and a co-author of the IPCC report. "It appears to be kicking into gear right now. That’s headline news," he told Reuters.

How might these conveyor-belt slowdowns affect us in Maryland? Nobody can say for sure, but scientists point to two global phenomena. One is weather. Because ocean currents redistribute heat around the planet, the resulting patterns of rainfall and drought can shift. Regions with established patterns of low rainfall (deserts, for example) could become wetter. That could leave less rain to fall in areas that counted on regular rainfall to grow crops. I have found no research reports that venture to say how things might change in Maryland but change they certainly could.

The other global phenomenon is productivity of the fishing industry. The turnover of sea water brings nutrients from the deep—organic matter of all kinds—up near the surface where most fish live. The nutrients support food chains up to the species we humans like to eat. With a slowed oceanic turnover, there would be fewer fish to catch.

The overall effects will be slow to come. But since humanity’s emission of greenhouse gases is still increasing—and is projected to keep increasing for years to come—those effects are essentially certain to arrive.

Read past editions of Science Matters