|

The Fall of the Banking House of

Annan-Horner

Michael Hillman

The

end of 19th and the beginning of the

20th century marked the most

promising and prosperous period in

Emmitsburg's history. This high

watermark owes its thanks in many

ways to two families: the Annans and

the Horners, whose names and good

work have all but been forgotten. The

end of 19th and the beginning of the

20th century marked the most

promising and prosperous period in

Emmitsburg's history. This high

watermark owes its thanks in many

ways to two families: the Annans and

the Horners, whose names and good

work have all but been forgotten.

In 1882, Andrew Annan, with his sons

Isaac S. Annan, James C. Annan and

son-in-law, Major 0. A. Horner,

organized the Annan-Horner Bank. For

40 years, through diligent loans and

investments, the bank brought

prosperity to the community. Sadly,

these great families lost

everything, including their

reputations, following the collapse

of their banking house in 1922.

To fully understand the impact of

the fall of the Annan-Horner Bank

banking house on those individuals

and the community at large we must

first step back in time and briefly

trace the roots and accomplishments

of these two great families.

The Annan Family

Robert Annan, the great-grandfather

of Andrew Annan and the founder of

the banking house of Annan & Horner,

was born in Scotland in 1742. He

studied theology at the University

of St. Andrew under Alexander

Moncrief, one of the original

founders of the

Presbyterian Church.

Licensed by the Associate Presbytery

when only nineteen years old, Robert

migrated to New York in the summer

of 1761 where he remained for

nineteen years having four

congregations under his charge.

In 1764, Robert married Margaret

Cochran, daughter of William

Cochran. In 1762, William Cochran

purchased the western and northern

portions of Carrollsburg, an area

which now encompasses most of the

land west of Track Road up and north

to Fairfield, Pa. (In 1754, Samuel

Emmit had purchased the smaller

eastern part of this tract).

Margaret Cochran bore Rev. Annan two

sons: Robert II and William, both of

whom became physicians.

Robert was a firm believer in the

colonial cause. According to family

legend, he was known far and wide

for his frequent and colorful

denunciations of the British

Government. He was often visited by

Washington, Hamilton and Lafayette.

One can only wonder what might have

been said as these great figures sat

and talked of the events shaping

their world.

Robert Annan II was a graduate of

Brown University. Following

graduation, he studied medicine

under Dr. Rush of Philadelphia, the

foremost doctor of the time. Upon

his death Robert's grandfather,

William Cochran, passed his Tom's

Creek Hundred Estate on to Margaret

and her sister. The estate

eventually came into the hands of

Robert via Margaret, whence it

became know as the Annan Homestead.

Upon completing his studies, Robert

established his practice in

Emmitsburg, where he met his wife

Mary Cochran. Mary and Robert II had

11 children. The youngest, Andrew,

was born in the Annan homestead in

1805.

[Historical Note: Like his neighbor,

William Emmit, Robert tried his hand

at "town farming"-Robert's town,

called Annandale, was laid out

west-south-west of of William

Emmit's new town-"Emmitsburg"-half

way toward present day Mount St.

Mary's University. While Robert was

able to sell some lots in Annandale,

he was unable to repeat William

Emmit's success and eventually gave

up on the idea. The area where he

had hoped to build his town,

however, still bares the name

Annandale, as does the present day

road that skirts its western

boundary.]

We

know very little about Andrew Annan

other than that he followed the

footsteps of his father and became a

physician. In ____ he married Anna

Motter, with whom he had six

children: Robert L., David, Isaac

S., Andrew A., James Cochran and

Anna Elizabeth. We

know very little about Andrew Annan

other than that he followed the

footsteps of his father and became a

physician. In ____ he married Anna

Motter, with whom he had six

children: Robert L., David, Isaac

S., Andrew A., James Cochran and

Anna Elizabeth.

Robert L. Annan

was born on February 22, 1831. In

1849, he entered Washington and

Jefferson College. Upon graduation,

he studied medicine at the

University of the City of New York.

In 1855, he returned to Emmitsburg

and joined his father's practice.

For the next fifty-two years, he

served the Emmitsburg Community.

Concerned with the welfare of the

community at large, Dr. Annan was

often sought out for his advice and,

because of his education, was made a

trustee of the public schools. In

1869, he married Alice Columbia

Motter, the daughter of Mr. Lewis

Motter. Following her death in 1878,

he married Miss Hessie Birnie.

Between the two, he raised eight

children.

Isaac S. Annan was educated in the public

schools of Emmitsburg. When

twenty-years-old, he became a clerk

in the general dry goods store of

George W. Rowe. Following Rowe's

retirement in 1856, Isaac became the

store's proprietor and changed its

name to I. S. Annan & Company.

In 1858, Isaac's brother James

joined the firm. The store became

known as I. S. Annan & Brother. In

1880, having profited handsomely

from the store, Isaac turned the

day-to-day operations of the store

over to his brother James. Free of

the duties of maintaining the store,

he turned his attention to one of

the most pressing needs of the

community: clean drinking water. In

1880, Isaac, organized the

Emmitsburg Water Company.

James Cochran Annan, was born in

1836. He was the junior member of

the firm of I. S. Annan & Brother.

Like his brothers, he was active

member of the Emmitsburg

Presbyterian Church. For thirty

years, he was superintendent of the

Presbyterian Sunday School and along

with his brother Robert, one of the

Church's trustees.

In ____ James married Rosa J.

Stewart, a member of an old and

well-known Scottish-Irish family of

the Cumberland Valley, Pa. Rosa and

James had _____ children: the _____

James Stewart, was born in _______

Anna Elizabeth, the youngest child

of Andrew and Anna Annan, was born

_________. In 1878, Anne married

Oliver Horner, with whom she had ___

children. Andrew Annan Horner, the

_______, was born _____.

The Horner Family

As in the Annan Family, the roots of

the Horner family can be traced to

the original settlement of the area.

In 1753, John and Mary Williams

joined the growing community of what

was then called the Tom's Creek

Hundred. With the help of their

son-in-law, William Shields, John

and Mary acquired one of the finer

tracts of land in the area, Wilson's

Fancy. Wilson's Fancy now

encompasses Emmit Gardens and Silo

Hill. [First

settled in 1733 by John and Mary

Wilson, Wilson's Fancy was the very

first homestead in what would later

become know at the Tom's Creek

Hundred area.]

After his death in 1756, John

Williams deeded the land to his

three youngest children: Eleanor,

Ester and Henry. Over the ensuing

years Henry acquired his sisters'

shares and in the early 1800's

renamed the combined properties

"Fort Henry."

With the onset of the Revolutionary

war, Henry, then 33, was elected

second lieutenant of the

Game Cock

Company, one of the two

companies raised in immediate area,

both of which belonged to a regiment

commonly referred to as "The

Flying Camp Battalion"

Henry's company was commanded by his

neighbor, Capt. William Blair.

Henry's brother-in-law, William

Shields, commanded the second

company.

When Capt. Blair was wounded at the

battle of Brooklyn Heights,

Henry

assumed command of the "Game Cock"

company. Under Henry's

command,

the

company participated in many

hard-fought battles and,

because of this, they drew the

attention of George Washington and

the admiration of Gen. Lafayette, to

whom they reported during the final

assault on the siege of Yorktown.

When the war was over, Henry

returned to Emmitsburg and turned

his attention to his farm and

community affairs. In _____, Henry

oversaw the building of the bridge

over the Monocacy between Taneytown

and

William Emmit's new town of

Emmitsburg. Henry also

severed as local Justice of the

Peace, and many deeds of this period

bear his name.

In 18___, Henry married Jane

Witherow Cooper. Henry and Jane had

one son, _______, who showed little

interest in farming the Fort Henry

estate. Instead, he presided over a

business career in Frederick, were

he quickly rose to prominence.

When the war was over Henry returned

to Emmitsburg and turned his

attention to his farm and community

affairs.

Jane's sister, Sara, married

Alexander Love Horner II, whose

parents had settled on a farm just

across the Pennsylvania-Maryland

line. Sara and Alexander had four

children: George, Mary, David and,

in 1817, their last child, Alexander

L. Horner III.

In 1825, Sara Horner died, followed

six year later by her husband,

Alexander. After, the death of their

father, the Horner children went to

live on the great Fort Henry estate

of their now-widowed Aunt Jane. In

1853, a year before her death,

Jane sold Fort Henry to

her youngest nephew, Alexander.

Following the outbreak of the Civil

War, Alexander's nephew,

Oliver enlisted as a

private in Company C of Cole's

Maryland Cavalry. Following the

resignation in 1862 of his cousin

John Horner, Oliver assumed the

leadership of the Calvary Company.

Under Oliver's leadership the

exploits of the mostly Emmitsburg-staffed company became legendary.

Promoted repeatedly for efficiency,

bravery and meritorious conduct, he

ended the war with the rank of Major

and joined Henry Williams in the

ranks of true American heroes who

proudly called Emmitsburg home.

Just like his great uncle Henry

Williams before him, following the

war, Oliver returned to Emmitsburg,

Md., where he engaged in various

mercantile pursuits. He was

appointed Emmitsburg's postmaster in

1869. He resigned that position in

1877 to become United States

storekeeper of customs in Baltimore.

A post he held until 1882.

In 1878, Oliver Horner married Anna

E. Annan, the daughter of Anna and

Andrew Annan. In 1882, he returned

to Emmitsburg and was immediately

elected president of the Emmitsburg

Board of Commissioners. It was under

his tenure that the new Frederick

County Board of Health first raised

concerns over the quality of

drinking water available to the

residents of the town. As President

of town's Commissioner, Oliver

facilitated the town's ceding of a

right of way for the laying of water

pipes to the new Emmitsburg Water

Company that his brother-in-law,

Isaac Annan, owned.

The Formation of the Banking

House of Annan & Horner

In 1882, Andrew Annan, with his sons

Isaac S. Annan, James C. Annan, and

son-in-law, Oliver Horner, organized

the Annan & Homer bank. I. S. Annan

served as president; Oliver Horner

served as cashier.

In 1883, Isaac's son Edgar joined

the new banking firm. Born on July

4, 1865, Edgar was educated at New

Windsor, Md. In 1883, Edger gave up

his studies and began work at the

bank. Following the death of in 1897

of Oliver Horner, Andrew became the

bank's cashier.

In 1902, five years after Oliver

Horner's death, his son, Andrew

Annan Horner, succeeded to his

father's interest in the banking

firm. Born in March 1881, Andrew

Annan Horner attended public grammar

school and the High School of

Emmitsburg. Unlike his cousin Edger,

Andrew completed his education at

Eastman's Business College at

Poughkeepsie, Ny., where he majored

in banking.

In 1909, Andrew married Helen Bruce

Morrison, daughter of William and

Helen (Agnew) Morrison, of

Emmitsburg, Md.

[Historical Note: William Morrison

was the son of Emmitsburg's

wealthiest landholder, David

Morrison, who was married to a

sister of Robert Morris, the

financier of the American War of

Independence.]

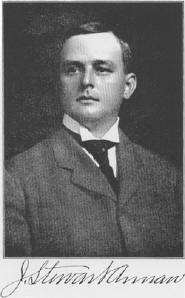

In

_______,

James Stewart Annan, the

_____ son of James Cochran and Rosa

Annan, joined the banking firm. Know

as J. Stewart Annan, he attended New

Windsor College, the Chambersburg

Academy, in Chambersburg, Pa., and

Lafayette College, Easton, Pa. Upon

the completion of his education, J.

Stewart returned home, and engaged

in various occupations, including

the management of his farms that

totaled over 700 acres. In

_______,

James Stewart Annan, the

_____ son of James Cochran and Rosa

Annan, joined the banking firm. Know

as J. Stewart Annan, he attended New

Windsor College, the Chambersburg

Academy, in Chambersburg, Pa., and

Lafayette College, Easton, Pa. Upon

the completion of his education, J.

Stewart returned home, and engaged

in various occupations, including

the management of his farms that

totaled over 700 acres.

In addition to being on the board of

the Bank, J. Stewart Annan was also

a director in the People's Fire

Insurance Company of Frederick

County, the Emmitsburg Water

Company, the Emmitsburg and

Frederick Turnpike Company, and in

1907, he was elected to the office

of Commissioner of Frederick County

for a four-year term. He was

re-elected for a second term in

1911.

In 1896 J. Stewart Annan married his

cousin Andrew's wife's sister,

Elizabeth Morrison.

Shortly after

their marriage, the pair purchased

the old Horner home place, ‘Fort

Henry.'

A

wealthy man, Stewart Annan had the

means to turn Fort Henry's "Mansion

House" into a true mansion. In the

Victorian style of the time, he

added an eye-catching turret with

curved windows and steep-like roof.

He added a formal dining room on the

first floor and, adjoining it, he

included a butler's pantry. In 1897,

he added an entire rear wing. On the

east side of the rear addition, he

built first and second floor

porches. He also installed an oval

"Tiffany" stained glass window on

the second floor, also

characteristics of the Victorian

times. A

wealthy man, Stewart Annan had the

means to turn Fort Henry's "Mansion

House" into a true mansion. In the

Victorian style of the time, he

added an eye-catching turret with

curved windows and steep-like roof.

He added a formal dining room on the

first floor and, adjoining it, he

included a butler's pantry. In 1897,

he added an entire rear wing. On the

east side of the rear addition, he

built first and second floor

porches. He also installed an oval

"Tiffany" stained glass window on

the second floor, also

characteristics of the Victorian

times.

J. Stewart and his wife Elizabeth

were the closest thing Emmitsburg

ever had to royalty. They lived

extravagant lives, funded by the

profits they received from all their

business investments. Elizabeth was

a frequent visitor to the most

prestigious stores in Baltimore and

the couple thought nothing of paying

more for a simple light fixture than

most residents in the town earned in

a year.

Under the tutelage of these three

men, the bank prospered. They loaned

liberally to friends and neighbors,

and reinvesting their profits back

into the community. In a short

matter of time, the Annans and

Horners became controlling

stockholders in the Emmitsburg Water

and Turnpike Companies and,

following the bankruptcy on the

Emmitsburg

Railroad in 1897, they

assumed a significant financial

holding in it as well. They also

invested heavily in local farms and

orchards. In ___, they purchased the

Blue Mountain Apple Orchard, which

held great promise of even more

profit.

World War I - Boom and Bust in

the American Farming Comminutes

When

the war in Europe began in 1914, the

United States was in a recession.

European need for goods such as food

and munitions helped end the recess

in and set the stage for a long

economic boom. When

the war in Europe began in 1914, the

United States was in a recession.

European need for goods such as food

and munitions helped end the recess

in and set the stage for a long

economic boom.

The destruction of European farms

benefited American farmers. Excited

by the rise in prices for food, they

borrowed heavily to buy more land

and expand production.

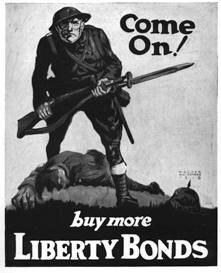

America's entry into the war in

April 1917 unleashed a torrent of

Federal spending, most of it funded

by Liberty War Bonds. The bonds were

denominated in small amounts, i.e.,

$100s and sold by investment

bankers. The small denominations

opened the floodgates to a whole new

group of investor, namely small

community banks like the Annan-Horner

Bank.

To ensure the Liberty-Bonds sold

well, the federal government

pressured the newly founded Federal

Reserve to keep its lending rates

low. Looking to cash in on the

higher returns on the Liberty Bonds,

many small banks, including the

Annan-Horner Bank, borrowed heavily

from larger banks and invested in

these bonds.

In addition, many of the bank

customers withdrew savings from

lower interest savings accounts and

purchased their own bonds. In

withdrawing their funds, the banks

customers had a significant impact

on the working capital of the bank.

As long as interest rates stayed

low, the boom in the high yield

Liberty Bond market remained strong.

When they needed to raise cash, the

Annan-Horner Bank found a ready

market for its Liberty Bond holding.

As such, liquidity was not an issue.

Unfortunately for the Annan-Horner

Bank, as well as other holders of

Liberty Bonds, the decision of the

Federal Reserves to hold interest

rates led to a rapid growth in the

money supply, setting off an

inflationary boom. Following the

cession of hostilities in Europe, to

address the inflationary spiral, the

newly established Federal Reserve

System set in motion drastic

deflationary steps.

The Fed's plan included the raising

of short-term interest rates and the

liquidation of the Liberty Bonds,

which would further reduce the money

supply. Raising interest rates,

however, dramatically affected the

value of the fixed-interest Liberty

Bond. As Interest rates rose, the

value of the bonds plummeted.

As the Federal Reserve began to

enact its second phase of its

deflationary plan, the calling in of

loans, banks like the Annan-Horner

Bank were forced to sell their

Liberty Bond holding at below face

value. Well-funded big estates and

banking institutions purchased the

depressed bonds by the hundreds of

millions with heavy losses to

innocent original purchasers.

As Interest rates continued to

increase, small banks and people who

had Liberty Bonds and were trying to

hold them were forced to sell them

at whatever they could get. Needless

to say, the decision of the central

bank had a chilling effect.

Adjustments throughout the economy

were sudden, erratic and severe. By

Dec 7, 1920, the value of Liberty

Bonds hit a record low.

While all Liberty bondholders

suffered, farmers were especially

hurt. Wartime demand for food and

agricultural raw materials had

increased the prices of farm

products. Higher prices had

stimulated farmers to borrow heavily

and invest in additional land and

equipment-most of this purchased on

easy credit that was meant to be

guaranteed by the rising farm

incomes.

Farms were the first thing to

recover in Europe following the end

of WWI and, with them, the need for

American food stocks evaporated

almost overnight. Shut out of the

European market, the domestic

oversupply of food stocks led to a

drastic fall in the prices of farm

products, which directly translated

into declines in farm income. The

fall in food prices undercut the

farmland prices and meant that many

farmers had difficulty paying

interest on their loans, leading to

a mortgage crisis in the farming

community.

Failures and foreclosures followed,

including many locally like the

Zacharias Family that lost their

farm

Single Delight, which had

been in the family since the first

European settlers stepped in the

area.

Already pressed by losses form

Liberty Bonds, many small banks in

farming communities were unable to

bear the brunt of this second blow

and failed. The Annan-Horner Bank

did not escape this fate, and

according to its own records was

insolvent at the close of 1920. The

bank 1920 statement, prepared by

Edger L. Annan, showed that the bank

had absorbed its capital and

surpluses of $20,000, and was

$40,000 short in accounts. As bad as

this might sound, this loss was only

a paper loss and would only become

actual if the bank was forced to

sell its liberty bonds at the

depressed prices.

Word of the condition of the Annan-Horner

Bank was kept closely guarded and

few knew of its dire straights. The

Annan-Horner Bank families placed

their hope in the return of the bond

market; the profitability of their

orchard and the water company

investments; and the continued

loyalty of their customers. These

were customers who, in spite of

declining farm incomes, had

heretofore not succumbed to

withdrawing their savings from the

bank. As long as depositors did not

need to withdraw their money, there

would be no need to cash in the

Liberty Bonds and the bank would

survive.

The Perfect Financial Storm

However, time and weather were not

on the bank's side. On April 1921,

two nights of freezing temperatures

destroyed 75% of the county fruit

crop. The cash crops many farmers

depended on to fund themselves until

the fall harvest were wiped out. The

entire cherry, peach, pear and plum

crop, along with most varieties of

apple were hit the hardest. The late

frost also killed the winter wheat

crop, which placed additional

financial burden on local farmers.

Robbed of their spring cash crops,

farmers began to withdraw savings to

cover operating costs. To cover

withdrawals, the bank was forced to

sell some of its Liberty Bonds at

the depressed prices, forcing it

deeper into a financial abyss.

To add insult to injury, the late

spring frost was followed by drought

that lasted well into August and was

described by many as the worst

drought ever experienced. In July,

the area received less then 1" of

rain versus its normal 6 inches. Hay

crops, a vital staple for livestock,

produced only stubble. By August,

the drought was being called the

worst in three years, and water use

restrictions were put into effect

throughout Frederick County.

To limit their losses, the bank

began to call in loans. In April,

the bank seized the property of a

Callahan. In 1917, the bank had

placed a lean on the property

following the failure of the Blue

Ribbon Egg Company, which Callahan

had funded with a loan from the

Annan-Horner Bank.

May 14, 1921, the property was

subsequently sold at the public

square in Emmitsburg. Andrew A.

Horner represented the bank and was

questioned as to the correctness of

the title, to which he replied was

good. Based upon this declaration,

Dr. Jamison, a prominent physician

in town, bought the property.

About the same time, in an attempt

to raise badly needed capital, Annan-Horner

Bank filed for a charter as a state

bank. It was to have a capital of

$50,000 with a surplus of $25k. The

money was to be raised by the

selling of stock at a subscription

price of $15, though the face value

of the stock was only $10 share. The

extra $5 was to be used to establish

a surplus fund.

Shares for the bank were heavily

marketed to the residents of

Emmitsburg. For many, this was the

first opportunity to hold a share in

a company. Many residents who bought

shares did so by paying for their

shares by drawing upon savings in

their savings accounts. In doing so,

they inadvertently helped convert a

significant portion of the bank's

outstanding debt. In this case, it

was money owned to its depositors to

shareholder equity.

Exchanging debt for equity is a

frequent strategy used in resolving

high profile bankruptcies today.

Creditors agree to trade what is

owed to them in exchange for shares

and, with them, control of the

company. As creditors have a higher

priority in receiving their money

than stockholders, if the

institution should fail, the

decisions to accept such a deal only

comes after extensive research into

the assests of the company and its

ability to survive in its restricted

form.

Whether the residents of the town

who traded their savings for stock

in the Annan-Horner Bank understood

the risk they were taking or not

will probably never be known.

However, it is reasonable to ask

whether they would have been so

willing to part with their

hard-earned savings had they known

the true status of the bank's

financial condition.

Unfortunately, since the

Emmitsburg Chronicle,

which had so effectively

chronologized the events of the

community for the past 32 years, had

ceased operation the year before,

the outcome of the stock offering

was unknown, as well as what

happened over the next two months.

It is only through later court

testimony and newspaper's reports

that we learn that the Annan-Horner

Bank suspended operations on August

24, 1921, and, on October 21, its

accounts were assumed by the

Farmer's State bank.

Did the bank openly fail or was it

simply taken over by the Farmers

State Bank, as that bank seized upon

the opportunity to establish a

presence in Emmitsburg? Several

clues point to the later. First,

Andrew Annan, the cashier for the

Annan-Horner bank, was retained as

the cashier for the new Farmers

State Bank. Had the bank openly

failed, it is doubtful they would

have retained him.

Second, the Annan-Horner Bank

continued to lend money. On November

21, a month after being "succeeded

by the Farmer's State Bank," the

bank, under the name Annan & Horner,

Inc., lent Albert Wetzel and his

wife $140. The note, payable in 90

days, was subsequently endorsed to

the Baltimore Commercial Bank as

collateral security for a larger

loan of several thousand dollars

from that bank to the Annan Horner

bank.

Lastly, less than a month after

ceasing operation, Mrs. Andrew A.

Annan, president of the Emmitsburg

Democratic Women's Club and wife of

__________ , was elected

representative to the Democratic

State Convention. Again, had the

bank openly failed, it would be

doubtful that it could have secured

such a victory with the losses

residents would have occurred.

The year 1922 brought no relief to

the Banks hard pressed farmer

customers. April, usually one of the

wettest months of the year, saw only

one inch of rain. Once again, a late

frost destroyed a considerable

portion of peach, apple, cherry and

pear crops (upon which the farmers

banked so heavily), as well as the

early vegetables in the gardens. In

increasing numbers, farmers had to

turn to savings to make ends meet.

The Collapse of the Banking House

of Annan-Horner Bank

Up until this time, the bank

suffered primarily from events

outside of its control, but, with

the finances becoming increasingly

tenuous, certain questionable

actions of the bank (whether

intentional or not) cast suspicion

on its veracity, setting the stage

for the collapse of the bank.

A few days before the 18th of

February, 1922, the Baltimore

Commercial Bank returned the Albert

Wetzel note to the Annan-Horner Bank

requesting that they substitute

other collateral in place of it. On

February 18, Albert Wetzel, as

required, went to the bank to repay

his note. After making the payment,

he was informed that the actual note

was temporarily missing, but "not to

worry, it would be found and

delivered to him."

Contrary to the bank's statement, a

few days after receiving Wetzel's

payment, the bank returned his note

to the Baltimore Commercial Bank,

falsely stating the note was

uncollected.

Several months later, the Baltimore

Commercial Bank sued Wetzel and wife

and obtained a judgment against them

for $140. While there is no record

of Mr. Wetzel's response upon

learning that a lean had been placed

against him, one can only assume

that word spread quickly through the

community.

Two months later, and before the

Baltimore Commercial Bank brought

suit against Wetzel, the Annan-Horner

Bank lent $3,000 to George Smith,

who pledged the $2,300 in his

savings account with the Annan-Horner

Bank as security collateral for the

loan. The loan was no sooner agreed

to when it was resold at a discount

to the Baltimore Commercial Bank-the

bankbook being delivered along with

the loan papers in the case that any

money be taken from the account.

When the note came due in June,

Smith offered to pay the balance due

on the note, $700, provided the

Annan-Horner Bank would accept his

deposit book with the bank at its

face value of $2,320 with accrued

interest. The offer was refused.

Smith was told that the note was in

the hands of the Baltimore

Commercial Bank and settlement would

have to be made with that bank. The

bank refused to allow him to

withdraw his savings without his

bankbook and, shortly thereafter, a

lean was placed against Smith for

the defaulted note.

Given these questionable events,

which had begun to weigh heavily

upon the public's belief in the

integrity of the bank, one can only

imagine what went through everyone

minds on May 6, 1922, when they

awoke to headlines in the Frederick

Post that the local Union Bridge

Bank, one similar to the Annan

Horner Bank, was short $150K.

For the next few weeks, newspaper

headlines blazed with allegations

that the cashier had managed to

cover the missing funds every time

the bank was examined. It was only

after his activities had raised

suspicion that the president of the

bank requested the investigation,

whereupon the deficiency in funds

was discovered.

In a futile and fatal last-ditch

effort to raise capital, on

September 22, the Emmitsburg Water

Company, which was controlled by the

Annan-Horner families, raised the

water rates. The public outcry

against the rate increase was swift

and severe. With it, any sympathy

for the plight of the two families

vanished.

Within days, a leading attorney in

town, Vincent Sebold, filed suit

against the rate increase with the

State Public Service Commission. The

petition was signed by 2/3 of water

users, as well as the non-family

member of the Water Company Board.

While the bank might have been able

to explain away the Smith and Wetzel

fiascos as mere oversights, when Dr.

Jamison found the property he had

purchased five years earlier from

the Annan-Horner Bank (which at the

time they claimed had a clear title)

was under threat of Sheriff sale,

the bank lost all credibility with

the citizens of the town.

Unbeknownst to Dr. Jamison and

contrary to public statements of the

bank at the time of the original

sheriff's sale, the title to the

property sold to Dr. Jamison was not

clear. The bank had a second lean on

the property. Several months after

winning this lean, the Annan, Horner

Co. sold it to the Farmer's and

Mechanics National Bank of Frederick

to secure a loan to them.

When it entered bankruptcy, the

Annan-Horner Bank ceased making

payments on the loan to the Farmer's

and Mechanics National Bank. In

response, the Farmers and Mechanics

National Bank directed that the

property be sold by the sheriff.

While Dr. Jamison managed to delay

the sale, the damage was done.

In November, Dr. Jamison filed a

petition with the circuit court

alleging that the bank had

liabilities in excess of assets in

excess of $110,000 and, as such, was

insolvent. A few days later, the

bank admitted the insolvency and

offered no objection to the

appointment of a receiver, which was

appointed on Dec 4th.

Three days later, a petition was

filed with in Federal court by the

attorneys for Albert Close, Mary

Martin and Ersa Six. The three

neighbors all had savings accounts

with the Annan Horner Bank. Like

Jamison's petition, their petition

alleged that the banking firm was

insolvent and that the bank had

committed an act of bankruptcy by

allowing a receiver to be appointed

to take charge of the property and

affects.

Upon reviewing their petition, the

judge issued an order giving the

Annan Horner bank until Dec 23rd to

reply or they would be adjudged on

involuntary bankrupts. Once judged

bankrupt, the case would be handed

over to Federal authorities, which

the depositors felt were better

qualified to handle the case than

the locally appointed receiver.

On December 11, four days after the

receiving the order from the Federal

court, Andrew A. Horner, cashier of

both the Annan-Horner and Farmer's

State Bank, submitted his

resignation.

The Dec 23rd deadline came and went

with no reply from the Annan Horner

Bank. As such, the Annan Horner Bank

was declared involuntarily bankrupt.

Ten days later, a fire destroyed the

barn at the bank's Blue Mountain

Orchard Company. Six horses, two

mules and 14 cows were lost with the

barn, together with a large quantity

of hay and feed and farming

equipment. The total loss of

livestock is estimated at $3,500,

hay and feed at $1,000, and farming

equipment at $800. Along with the

barn and its content went a silo and

a shed. The total loss is estimated

at upwards of $10,000.

According to Samuel Long, who

tenanted the farm, all was well when

he retired Sunday evening. When he

arose on Monday at 5 am, he heard

the crackle of flames and looked out

to see the barn a flaming mass. "The

entire upper part of the barn had

already caught fire." Whispers of

arson quickly spread through the

town.

On March 17, Arthur Willard, who had

been appointed by the Federal court

as bankruptcy referee, began his

public hearings. The object of the

hearings was to ascertain the assets

of the bank and individual members

of the firm. The trustees for the

creditors and depositors: State's

Attorney General Alexander

Armstrong, John S. Newman, and

Emmitsburg Lawyer Vincent Seabold

would turn the assets into cash for

the benefit of the creditors and its

300-400 depositors.

The bank's assets consisted mostly

of personal loans to local residents

and equity in real estate over and

above montages on dwellings in

Emmitsburg. In addition, the bank

claimed the 255-acre Blue Mountain

Apple Orchard to be worth $20,000 to

$25,000. However, against the

Orchard property were two montgages

equaling $40,000. One held by John

Hollinger for $15,000 and other by

the Baltimore Commercial Bank for

$25,000.

On April 27, Edgar L. Annan and

Annan Horner appeared as witnesses.

It was during this hearing that

residents of Emmitsburg first

learned that the bank was

technically insolvent as early as

1920, a full year after they had

been lulled into buying stock in it.

In his defense, all that Edgar Annan

could say was he thought the figures

wrong even though they were his

figures.

In their testimony, the cousins

claimed that poor investments,

mainly in the Blue Mountain Orchard,

a garage, and other investments,

especially Liberty Bonds, were

responsible for the condition of the

bank's finances.

At the resumption of the hearings

four days later, it was disclosed

that, before the finical conditions

of the bank had been made public,

Edgar Annan had sold his place of

home and place of business in

Emmitsburg for approximately $11,000

and had invested the proceedings in

the name of his wife and two

daughters. The trustee immediately

sized upon this revelation and

opened an investigation into the

transaction with the view of having

the proceedings declared a part of

the assets of the defunct bank.

In June, the bankruptcy referee

began to investigate the bank's

handling of transactions involving a

$900 loan to Francis S. K. Mathews

and another for $200 for Albert C.

Wetzel.

The bank had discounted the two

notes, bundled them along with other

notes and sent them on to the

Baltimore Commercial Bank as

collateral for a loan. When the

notes came due, they were sent to

the Farmers' State Bank in

Emmitsburg for collection. Upon

receipt of the notes, he notified

Matthews and the latter borrowed

$900 on a note from the Farmer's

State Bank and paid the Annan-Horner

note. Instead of turning this amount

over to the Baltimore Commercial

Bank, he credited the amount to the

Annan-Horner Bank.

Later, the Baltimore Commercial Bank

notified the Farmer's State Bank

that nothing had been heard from the

Matthews and Wetzel notes sent for

collection. Officials of the

Farmer's State Bank pressed Horner

as to his actions and gave him 24

hours to make good the amount under

threat of suing his bond. He secured

the money and turned it over the

Farmer's State Bank.

On ________ 1923, the bankruptcy

referee appeared before a grand jury

and won an indictment charging

embezzlement, false pretenses on the

handling of the Mathews and Wetzel

notes, and then later, handed down

four more indictments against Andrew

Annan and Andrew Horner stemming

from charges made based on the

non-payment of claims aggregating

$154. The largest claimant was the

bank's principle nemesis: Dr.

Jamision.

Arrest & Trial

On the afternoon of Thursday, Sept

20, 1923, Edgar L. Annan and Annan

A. Horner were arrested by Deputy

Sheriff Charles W. Smith. Following

their arrest, they were brought to

the Sheriff's office where bail for

Horner was set at $2,000 and fpr

Annan at $1000.

Thomas Baumgardner bailed out Horner

and Robert L. Annan bailed out his

brother Andrew.

The arrests caused a great deal of

excitement in the town. A warrant

for the arrest of Annan Horner had

been sent to the Deputy Sheriff

Addlesburger on Wednesday. The

warrant for the arrest Edgar Annan

was sent to Baltimore, where he had

moved.

On Thursday morning, Andrew drove to

Emmitsburg from his home in

Baltimore, where he had moved two

week prior, to address some business

matters. Upon arriving in town, he

was arrested. Horner was arrested as

he walked down Main Street near the

center of the town.

When it became known that the

arrests had been made, a crowd of

several hundred people assessable at

the square to witness the officers

pass with the men in custody.

While it was generally known that

the grand jury had indicted the

former bankers, the utmost secrecy

was maintained on the part of the

State's attorney and court official

until the warrants were issued and

arrests made.

The specific changes made against

the two involved the settlement of

the estate of Charles Shuff. The

warrants charged that the bank

failed to pay certain creditors of

the estate and that the bank had

illegally obtained loans, old notes

that had been paid off or renewed.

After arriving at the sheriff's

office, Annan Horner retained former

State's Attorney Samuel Lewis, while

Andrew Annan retained Reno Harp. The

pair were subsequently transported

to Frederick, where they were

arraigned before a judge and

formally charged with false

pretense, larceny and embezzlement.

By 6:30 p.m., bail had been posted

and both men were on their way home.

On

Thursday, September 25th, Andrew

Annan's trial began. The courtroom

was filled to capacity, mostly with

residents of Emmitsburg. From the

very beginning, the prosecution and

defense clashed over how facts were

to be interpreted. It is called one

of the most completed cases ever to

be brought before the court because

much of the testimony involved

intricacies of reporting roles and

responsibilities of the Annan-Horner

Bank to its new owners the Farmers

State Bank. Following the Farmers

State Bank's take takeover of the

Annan-Horner Bank, the books and

records of the two were separate.

Many of the questions posed by the

prosecution involved why one account

was débuted or credited vice

another. On

Thursday, September 25th, Andrew

Annan's trial began. The courtroom

was filled to capacity, mostly with

residents of Emmitsburg. From the

very beginning, the prosecution and

defense clashed over how facts were

to be interpreted. It is called one

of the most completed cases ever to

be brought before the court because

much of the testimony involved

intricacies of reporting roles and

responsibilities of the Annan-Horner

Bank to its new owners the Farmers

State Bank. Following the Farmers

State Bank's take takeover of the

Annan-Horner Bank, the books and

records of the two were separate.

Many of the questions posed by the

prosecution involved why one account

was débuted or credited vice

another.

The complexity of the case was

demonstrated by the contention of

the defenses to the effect that the

transactions in question were

between a creditor and debtor and,

therefore, could not legally be

construed as embezzlement.

The State's case:

"While Horner was employed as

cashier of the Farmer's State

Bank, which was the agent for the

Baltimore Commercial Bank, he was

the recipient of two notes

aggregating $1,100, sent by the

Baltimore Bank to be collected

from the Annan-Horner Bank, which

was in the process of liquidation.

The notes are alleged to have been

received by Horner in May 1922.

One note was that of Francis

Matthews for $900 and the other

was that of Albert Wetzel for

$200.

Nothing was heard from the Farmers

State Bank until the following

December at which time the

Baltimore bank is alleged to have

gotten into communication with

officials of the Farmers' Bank.

The transactions between the two

banks involving the notes is

alleged not to have been known by

the other banking officials until

then.

When Horner was questioned about

the matter by his superiors he is

alleged to have said that the

transaction was "O.K.," but it is

alleged Horner was told that he

"would be given until morning to

make good," or the Farmers' State

Bank would sue his bond. Horner

then paid the money, but the

charge was, however, pushed."

The Defense's case

"When the Farmers' State Bank of

Emmitsburg took over the business

of the Annan-Horner Bank, the

State Bank Examiner instructed

that the accounts of the two firms

be kept separated. Before this

transaction however, the Annan-Horner

had borrowed a sum of money from

the Baltimore Commercial Bank in

which it was required to post a

20% collateral as added security.

Among the collateral deposited

with the Baltimore Bank were the

two notes of Francis Mathews and

Wetzel, money that had been

borrowed from the Annan-Horner

Bank.

Upon receipt of the notes, Horner

noticed the pair. Mathews and

Wetzel went to the Farmers State

Bank, of which Horner was the

cashier, and applied for a loan to

cover the original loans. With the

money form these new loans,

Mathews and Wetzel paid off the

Annan-Horner notes.

Horner then deposited the money

into the account of the Horner-Annan

Bank vice returning the funds to

the Baltimore Commercial Bank. The

justification for this action

according to the defense was the

Annan-Horner Bank was not required

to turn the money over to the

Baltimore Commercial Bank as that

bank still had in excess of 20%

collateral assurance. The money

was subsequent used to pay off the

Annan-Horner's debts during

liquidation."

The

Baltimore bank is then alleged to

have threatened the Farmer's State

Bank at Emmitsburg with suit because

the money was not paid. The

Baltimore bank claimed that the

Farmers State Bank was their agent

and, as such, was to have made the

collection. When the suit was

threatened it was alleged that the

$1,100 involved was paid over to the

Baltimore Bank by the Farmers State

Bank, which in turn demanded that

Horner make redress. Horner and his

wife then borrowed the $1,100 from

another bank in Emmitsburg, and

turned the money over to the

Farmer's State Bank.

On September 28 Andrew Horner got

the first good news in what probably

seemed a life time. "Not guilty of

Intent to defraud" was the verdict

of the court.

In presenting his basis for the

conclusion, the judge noted:

"The Annan Horner Bank and the

Farmer's Bank had been instructed by

the State Bank Examiner, after the

failure of the Annan, Horner & Co.

To keep all accounts separate. He

explained that the Baltimore

Commercial Bank held 20% more

collateral security than the amount

of the Annan-Horner loan and, for

this reason, it was appropriate to

apply the proceeds of the Mathews

and Wetzel notes to the insolvent

bank."

In

November, the referee took up the

case of sale of the families'

holdings in the Emmitsburg Water

Company, of which the members of the

bankrupt firm were large

shareholders. It was revealed that

the stock was pledged to the

Baltimore Commercial Bank. The

Baltimore bank agreed to sell the

stock to a group of citizens in

Emmitsburg led by the Hays family,

and to allow the proceeds above and

beyond its loan be applied to settle

account with the banks depositors.

On

Dec 4, the J. Stewart Annan's

property on the north side of West

Main Street, a two and ˝ story brick

dwelling, was sold at a sheriff's

sale to Elizabeth N. Annan for

$4,025. Andrew Annan Horner's house,

a two and ˝ story brick dwelling,

located on what is know as Shield

Addition, was sold to Helen Bruce

Horner for $3,025. The 234-acre

Annan farm situated about 3.5 miles

southeast of Emmitsburg on Keysville

road was withdrawn from the sale, as

the auctioneer deemed the prince

offered too little.

On March 8, 1924, Edgar Annan and

Andrew Horner finally got their day

in court for the remaining charges

and were found not guilty.

The embezzlement charges were based

on the non-payment of claims

aggregating $154. The largest

claimants were Dr. B. Jamision and

Dr. John Brawner.

It was shown by the testimony that a

large number of claims were paid by

the trustees and that four or five

claims remained unpaid. The unpaid

claimants, it was alleged, owned the

estate, and for this reason it was

testified and the trustees refused

to settle the claims. It also showed

that the trustees had ample funds on

hand from the estate in its hands to

pay the claims. Furthermore, it was

to shown that the commissions of the

trustees were not drawn from the

trustee funds, but remained and

constituted a balance above the

amount of the claims.

The prosecution, assisted by Author

Willard, set forth that the trustees

did not have from the estate

sufficient funds to pay all

claimants the charge of embezzlement

was based upon the amount to the

unpaid claims. However, the

prosecution's arguments didn't win

over the court.

In their finding for the defendants

the court said:

"Upon

the evidence we can have no

hesitation in rendering a verdict

of 'not Guilty' The funds to which

the charge of embezzlement in this

case refer to were aggregating

about $154 audited upon the claims

of two creditors of an estate

which the defendants were

administering as trustees. The

testimony clearly shows that the

pavement of the two dividends was

suspended by the trustees because

the creditors were indebted to the

trust estate. It was solely for

that reason and not because of any

criminal or fraudulent purpose

that the checks for the sums

mentioned in the indictment were

not delivered. The dividends on

claimed of numerous other

creditors were dully paid. The

trust funds were deposited by the

trustees in the bank of Annan,

Horner & Co, which was then

solvent. There was no

misappropriation of any part of

the money by the defendants, and

they did not even withdraw for the

bank account the commission to

which they were entitled. There

was sufficient balance in the

account to the credit of the

trustees to pay the dividends in

question. And, if the two

creditors had adjusted or

disapproved the counter-claims

against them, the checks for the

amount audited to them would have

been delivered and pain at any

time during the period of several

years that elapsed before the

failure of the bank in which the

funds were deposited. It would be

plainly unjust to deprive the

defendants of their liberty for

the conduct which has been

presented by the testimony in this

case." "Upon

the evidence we can have no

hesitation in rendering a verdict

of 'not Guilty' The funds to which

the charge of embezzlement in this

case refer to were aggregating

about $154 audited upon the claims

of two creditors of an estate

which the defendants were

administering as trustees. The

testimony clearly shows that the

pavement of the two dividends was

suspended by the trustees because

the creditors were indebted to the

trust estate. It was solely for

that reason and not because of any

criminal or fraudulent purpose

that the checks for the sums

mentioned in the indictment were

not delivered. The dividends on

claimed of numerous other

creditors were dully paid. The

trust funds were deposited by the

trustees in the bank of Annan,

Horner & Co, which was then

solvent. There was no

misappropriation of any part of

the money by the defendants, and

they did not even withdraw for the

bank account the commission to

which they were entitled. There

was sufficient balance in the

account to the credit of the

trustees to pay the dividends in

question. And, if the two

creditors had adjusted or

disapproved the counter-claims

against them, the checks for the

amount audited to them would have

been delivered and pain at any

time during the period of several

years that elapsed before the

failure of the bank in which the

funds were deposited. It would be

plainly unjust to deprive the

defendants of their liberty for

the conduct which has been

presented by the testimony in this

case."

Epilog

While Andrew Horner and Edgar Annan

were found not guilty of the charges

brought against them, they and their

families never recovered the good

will of the residents of the town

and moved on.

Proud men, they were terribly

humiliated to be forced to walk

through town in handcuffs in front

of people they had known all their

lives. Less than three days later,

Anna E. Annan Horner, the wife of

Major Oliver Horner, and the

matriarch of the families, died.

According to

Polly Baumgardner Shank,

the youngest daughter of Thomas and

Mary Morrison Baumgardner, and niece

of Andrew Horner and Edgar Annan,

and the oldest remaining relative,

"Aunt Anna died of a broken heart

over the whole thing."

Polly Baumgardner oldest brother,

Carl Baungardner drove Andrew Annan

and his family to Ohio where they

joined up with his cousins the

Agnews. The Agnews had a very

profitable potter works and, with

their help, Andrew rebuilt his life.

In 1931, he returned to Washington

where he built a reputation as a

highly successful and respected

lawyer. According to family legend,

he held the bible during the

swearing in of one of the

presidents.

All

of Andrew Annan's brothers and

sisters moved to their summer home

in Lynn Massachusetts following the

collapse of the bank and proceed on

with their lives. Andrew's brother

"O. A." would eventually rise to the

position of president of Pittsburg

Glass. Andrew Annan died in 1945.

Edgar Annan stayed in Emmistburg,

but disappeared from public life.

While never charged, nevertheless,

J. Steward Annan's personal fortune

and land were ceded to cover the

debts of the bank. As noted above in

1921, he was forced to sell his

Fort Henry mansion. In

1924, he lost all his farms,

including the

Long Field, which had

resided in the family for well over

100 years.

As

few people in the area had

sufficient funds to purchase J.

Stewart Annan's property, or the

other farms forced into bankruptcy

because of the repercussions of the

bank's failure, many local farms

passed into the hand of outsiders

and, with it, many old names that

had been uttered since the first

settlement vanished.

J.

Stewart Annan and his family moved

to Hagerstown where he and wife

lived a more modest lifestyle. He

eventually opened up an insurance

business.

In

1931, J. Stewart Annan, a man who

single-handily did more to enhance

the quality of life in Emmitsburg,

died.

Read

other stories by Michael Hillman

|