‘War really is hell,' says WW II pilot who served in Pacific

‘War really is hell,' says WW II pilot who served in Pacific

Harry D. Jones was struck by the sheer size of the thing.

It was April 7, 1945, and Jones, a Navy pilot, was flying his Avenger torpedo bomber just above the Pacific waves at more than 200 mph. His target was the Yamato, flag-ship of the Imperial Japanese Navy, the largest and most powerful battle-ship ever

built. The Yamato, which was nearly 900 feet long and 130 feet wide, was the last major warship left to the Japanese in the waning months of World War II.

"It looked like the Empire State Building in the water," recalled Jones, 84, of Hampden Twp. "That S.O.B. was big." It was also about to die.

Jones' Avenger was among scores of U.S. torpedo and dive bombers and fighter planes converging on the Yamato, which was on a suicide mission. The battleship had just enough fuel to reach the American forces that were invading Okinawa off the coast of

Japan.

With its enormous guns, the Yamato would have caused havoc had it reached the invasion fleet. The American airmen were determined to prevent that.

Jones, a member of Squadron VT-17 from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet, was one of the first to attack the hulking steel monster. "The weather was so bad, we shouldn't even have been flying," Jones said, recalling how he had to bore through mist

and rain toward the target. All the while, the Yamato threw up a curtain of anti-aircraft fire.

"I was going through puffs of smoke [from exploding shells] and the plane next to me got hit," Jones said. "I saw something fly off the engine cowling, and he crashed.

"The crew was all killed. They were replacements. It was maybe their second mission," he said. "The ball turret gunner on that plane had an 18-month-old daughter."

Jones roared on toward the Yamato. "I actually came in too fast," he said. "I went right over the bow of the Yamato and dropped my torpedo on a destroyer on the other side." He never knew whether he hit that enemy ship.

Other American planes slammed 10 torpedoes and 23 bombs into the Yamato, which finally exploded and plunged to the bottom of the sea, taking nearly 2,500 members of her crew with her.

For Jones, the episode. didn't end with the Yamato's sinking. About 10 years ago, through the Hornet's Web site, he met and befriended the daughter of the gunner whose plane was shot down that day. "She and her husband went out to where the Yamato sank.

She threw flowers on the ocean," Jones said.

The attack on the Yamato wasn't Jones' first or last mission. He'd already been in combat for six months, mostly conducting bombing raids on Japanese-held islands.

The Pittsburgh native was working for the FBI when he joined the Navy in 1942. A friend, a ham radio operator, helped him prepare by teaching him Morse code, which all pilots of the era had to master.

| During WWII, myself, and other Navy Aviation Cadets received part of our "ground school training" at Mt St. Mary's College. During the afternoon we went over to Waynesburg to receive flight training at Potteroff's Airfield. During that period of time, I met an Emmitsburg young lady, Valerie "Petie" Shorb. We corresponded during the war. After the war was over, we got married in 1946.

I was employed in Washington, D.C. and for many years, practically every weekend, with our children, we visited Petie's parents, Charles Shorb and Rose Shorb, who resided on North

Seton Avenue.. We, immensely enjoyed those visits to Emmitsburg.

My wife died in 1992, and is buried in Emmitsburg. She is survived by her sister Irene Zurgable.

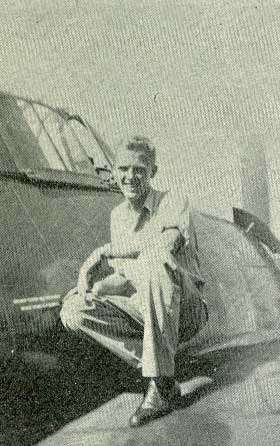

Harry D. Jones |

|

After flight training [in Emmitsburg], "I put in for torpedo bombers," Jones said. "I didn't think I had the ability to maneuver a fast fighter plane around."

The single-engine Avengers were tough rather than maneuverable or fast, and their three-man crews had one of the most dangerous jobs in the Navy.

Jones said he and former President Bush have a few things in common. The ex-president also was an Avenger pilot, and like Jones, his plane was hit by Japanese gunfire over the island of Chichi Jima. Bush had to bail out of his flaming plane and was

rescued by an American submarine. "The only time I was hit was over Chichi Jima," Jones said. "They shot an aileron off, but I made it back to the ship."

A closer call came one day as he sat in his plane ready to take off from the Hornet. A flaming Japanese kamikaze plane came roaring in on a suicide run and passed just over his Avenger, he said.

One mission that really stuck with him was flown as U.S. Marines fought to seize the island of Iwo Jima in the bloodiest battle in Marine Corps history, he said. "I could see that our Marines were getting slaughtered," Jones said. "War really is hell."

Jones, a widower with children and seven grandchildren, returned to the FBI after the war and became an agent, serving in Boston and Atlantic City. He became a bank security officer in New Jersey after retiring from the FBI.

His Navy service remains a focus of his thoughts, judging by the USS Hornet license plate on his Buick and the wartime photos and paintings that adorn his apartment.

The decades haven't dimmed those memories. "It seems like yesterday, truly," Jones said.