|

Cold War Warriors Spy Ships - Theirs and Ours

Commander John Murphy, USN, RET

They made for sensational headlines back in the 1960s and 1970s. "U.S. Spy ship Seized by North Korea", "Israelis Attack U.S. Spy Ship", "Soviet AGI collides with U.S. submarine near Rota". They made for sensational headlines back in the 1960s and 1970s. "U.S. Spy ship Seized by North Korea", "Israelis Attack U.S. Spy Ship", "Soviet AGI collides with U.S. submarine near Rota".

Who were these Cold War spy ships? For the most part they were Soviet or American ships that were specially equipped for a variety of intelligence missions. Visual and photographic, acoustic, electronic (radar etc.) and communications intelligence for the most part. They were usually equipped with fancy antennas and intelligence collection

paraphernalia.

Soviet Spy Ships

Technically speaking – any Cold War naval vessel was a potential spy ship, but the Soviet ships that were of the greatest concern to the U.S. Navy were those pesky, little, decrepit looking fishing trawlers that were interfering with naval operations worldwide. We called them AGIs (Auxiliary General Intelligence). The Soviets simply called

them "trawlers" (tral’shchiki). We gave them credit for being covert, but the Chief of the Soviet Navy (Admiral Konstantin Makarov) told me in 1988 "It’s all my government would give us. We wanted better ships, but were told they were too expensive." To the U.S. Navy – these small, ubiquitous AGIs were a genuine pain in the barnacles. They sat off all of our major base areas-

worldwide. A U.S. ballistic missile submarine could not enter or leave its base in Spain, or Scotland without being harassed by a Soviet AGI.. Our aircraft carriers could not conduct flight operations without an AGI cutting across its bow or sitting in the middle of it’s bombing zones. I increasingly came to believe that they just wanted to taunt us and ruin our day.

After the Cuban Missile Crisis, the U.S. Joint Chiefs had enough of these maritime pests. They authorized a "Counter AGI Program" with very clear guidelines as to what we could do and could not do to them. Plainly put … we could do just about everything- but we could not sink them. We could put destroyers alongside to "shoulder" them. Bump and

bruise them. Foul their propellers with steel wire or even melt the tubes in their electronic gear with high power electromagnetic radiations. They could get in the way of our operations, but they were going to pay for it. That was the plan. We tried some counter AGI operations in the mid 60s, but the AGIs proved adaptable and cagey. They may have looked like god-forsaken

pieces of junk, but they were manned by talented and capable crews. Scientists and signals intelligence professionals who were fluent in English. That sloppy looking captain that was in the wheelhouse was probably a Soviet Navy Commander or Captain who had just come from a destroyer in the Soviet Mediterranean Squadron. He, and all his crew had been carefully screened by the

KGB for political reliability and loyalty.

I took part in the first JCS-authorized operation against a Soviet spy ship in 1964. I was at the Atlantic Fleet Headquarters in Norfolk when I received orders to be the Officer in Charge of a Naval Security Group Detachment aboard the destroyer USS Robert A. Owens (DD 827). Our job was to keep a Soviet AGI - then operating near Norfolk, away

from tests of a new, U.S. Navy cruise missile (Harpoon). As a Russian linguist, I was given a special electronic system to monitor conversations from the AGI’s bridge area (wheelhouse). The "system" they gave me was called an ABC Sports Mike"system. It had just been introduced for use by ABC Monday Night Football TV crews. When we got alongside "our" AGI, all I got was noise

from an exhaust fan on my own ship. My ABC Sports Mike was not "directional"- It was totally omnidirectional. I gave up.

However, we continued to trail our target AGI for days as he moved northward towards Newfoundland. I became increasingly impressed with the shiphandling skills of the AGI’s Captain. We would try and come close alongside for photographic coverage and he would "spin on a dime" and head into the sun putting us at a disadvantage. Our destroyer

could not "spin" as nicely as an AGI.

We eventually figured out that our AGI was finishing a long, six month cruise and was looking for his replacement. Another AGI who was lurking somewhere in the midst of the huge, Soviet fishing fleet off Newfoundland. As we entered the Grand Banks, there were little fishing trawlers that looked just like our AGI – everywhere! Fortunately, we

were able to follow him because of his very distinctive navigation radar. It made a distinctive "hiccup" sound at the end of every sweep. When our AGI finally found his replacement – the two began exchanging boxes of classified material, food, and most importantly to them – vodka. I can still see the scene - topside on our AGI that day. Soviet scientists, sailors (i.e.

spooks), their mascot dog and a case of vodka. They waved and shouted greetings – in perfect English. They were going home to beautiful, downtown Murmansk. Our counter AGI operation was over.

It may seem like I "respected" the Soviet AGIs and to some extent I can see where they were serving a useful purpose. They were probably bringing home useful intelligence on our operations while making our life more difficult than we would have liked, BUT! ….. they were also taking unnecessary risks which were adding up in our "Incidents at

Sea" ledger. These incidents finally led to an Incidents at Sea Agreement between the U.S. and the USSR in 1972. This agreement clearly defined basic ground rules for the operations of Soviet and U.S. Navy ships, aircraft and submarines – on the high seas and in and around major base areas.

We were sick and tired of the Soviet spy ships interfering with our major exercises and general operations. AGIs were accidents that were just waiting to happen. They demonstrated poor seamanship and judgment to say the least.

I can recall one incident in the Sea of Japan in 1969 while serving aboard the carrier USS Enterprise. Our A-6 bombers were conducting what were called "wake bombing". Enterprise was in fight operations and running at high speed - up to 30 Knots or more. A large wake would appear aft of the ship and the A6’s would begin dropping unarmed 500

lb. bombs into the wake. Our duty AGI would complicate things by falling in 200 yards astern of the Enterprise and ride in the wake – taking in the show ….up close and personal. I don’t know what they were trying to prove, but it was risky behavior at best. Sometimes, we would have to suspend the bombing and send a destroyer out to "shoulder" the AGI away from the impact

zone. I am sure they took great delight in disrupting our training, but they would not be so smug if they could have heard the A6 pilots talking about them in their Ready Rooms after they came back aboard the "Big E". "Should’ve bounced a few off their antennas! See how they like that." Or …. "One good hit in the foredeck area of that pathetic piece of junk - would have sent

them straight to the bottom." Etc. Now that is what I call a real Counter AGI operation!

Our Spy Ships

Meanwhile, in the mid 1950s, we began creating our very own class of Spy Ship, known as the AGTR (Auxiliary General Technical Research). We were quick to point out that these were not spy ships - they were "Technical Research Ships". When we visited foreign ports and gave tours, our visitors would ask us "What are all those huge antennas for?"

We would respond "Tree research! We are conducting technical research of the forests around the world." Or something like that ….

By 1964, we had five AGTRs. Three were WWII Liberty hulls – USS Oxford, Georgetown and Jamestown (my future ship). The other two AGTRs were the more modern WWII Victory hulls – USS Belmont and Liberty. In WWII the single hulled Liberty ships were considered "expendable". They hauled cargo – if they made it… fine. To Murmansk in the Soviet

north or the Arabian Sea in the South. If not …. C’est la guerre. As spy ships they were big. Looked impressive. Carried lots of men and equipment. But were weakly armed. Mostly to repel hostile, boarding parties.

The first AGTR … USS Oxford became operational as the Cuban Missile Crisis was reaching its peak in 1962. Oxford was driving the Cubans crazy with her operations around the important naval base at Cienfuegos. She was "jumped" several times by heavily armed Cuban patrol craft. We had some anxious moments at the Atlantic Fleet Headquarters and

had to scramble Air Force and Navy jets from aircraft carriers and bases in Florida - to warn the Cubans that the had better not harm our spy ships. It was "brinksmanship" at its best. It worked. But, it also taught the U.S. military that it better keep a careful eye on these ships.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff required that NSA and the Navy keep everyone informed as to their operational schedules. From the earliest days …. We recognized that the AGTRs (and later the AGERs) were not your average naval ship. By the mid 1960s they were operating worldwide … probing potential, international hot spots. USS Oxford and Georgetown

covered Cuba and the Southern Atlantic. Belmont was sent out to the mid Pacific to snoop around the French nuclear tests and Jamestown checked out the Mediterranean and Africa. Liberty replaced the Jamestown in the Mediterranean. Meanwhile the Vietnam war was growing in intensity as the U.S. presence steadily grew in- country and at sea. Air Force and Navy strike aircraft

worked together to conduct major bombing (Operation Rolling Thunder) of the North Vietnamese logistics system down into South Vietnam through what was called the Ho Chi Minh trail.

I was the Operations Officer on USS Jamestown when she was assigned to replace Oxford off the coast of South Vietnam. We were assigned to conduct the first NSA-sponsored, electronic survey of South East Asia and Vietnam in 1964. Serving aboard a Liberty hull AGTR in a combat zone was nerve wracking. You were always aware that if you took a

torpedo or a mine in either of the major Operations Areas – the ship would quickly fill with sea water and you would "go down like a bomb". We operated very close to the Vietnamese coast in the Gulf of Siam and were constantly alert for attempts by the Viet Cong to sneak up in high speed, rubber boats in an attempt to place "limpet mines" on our hull. We operated due south of

Sihanoukville, Cambodia – right in the path of the main Viet Cong supply line flowing from Cambodia into the Mekong Delta region of South Vietnam. The saying was "We may own this place during the day, but the V.C. owns it at night."

Ironically, It probably was a good thing that the Israelis attacked a Victory hulled AGTR – USS Liberty on 8 June, 1967. My Liberty hull AGTR could not have survived such an attack. Israeli patrol boats made a direct hit with a torpedo in the USS Liberty’s communications center and the ship survived. But, not before 34 men died and 170 were

wounded. The Communications Officer, LT Jim Pierce, USN was killed instantly when the torpedo struck his spaces. Several months earlier, I was working to transfer Jim Pierce to a major communications center ashore. His dream assignment. I needed him immediately, but he asked me to leave him on board until after the 1967 cruise. That this would be his "sunset" tour. His final

tour in the Navy. Regretfully, for Jim, I agreed.

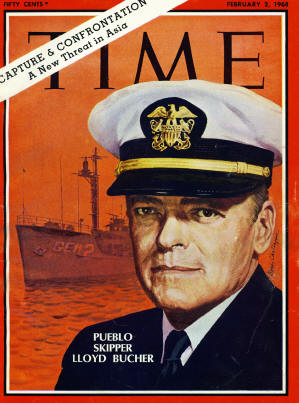

In the late 60s, the Navy created a new, smaller, less expensive, spy ship known as the AGER. There were three AGERs – USS Banner (AGER 1); USS Pueblo (AGER 2) and USS Palm Beach (AGER 3). In the late 60s I was responsible for assigning the Naval Security Group officers to these ships. We used Banner in North East Asia to keep an eye on the

North Koreans, Chinese and Soviets. Then we brought two more ships on line – USS Pueblo and Palm Beach. Since both ships were being introduced about the same time…. I let the officers pick their own ship. Those that preferred an East coast homeport - chose Palm Beach. Those that preferred the West coast went for the Pueblo. One of the officers en route to Pueblo asked me to

assign him to Emergency Ship Handling School before reporting. A special course for technical specialists in the Navy – to learn how to "drive a ship". I asked him why he would want to take such a course and he replied "Well, you never know. We might get attacked and the Captain might get wounded." I sent him to the course, but he never made it topside when the USS Pueblo was

captured on 23 January, 1968.

I find it sadly ironic that – all of our AGTRs and AGERs are gone – except for USS Pueblo that remains a ship of the U.S. Navy – tied up as a tourist attraction in Pyongyang, North Korea.

The others? I understand, they were towed out to sea and sunk, They became undersea "barriers and reefs". It was a particularly poignant moment for me, was when I was asked to visit USS Liberty in Norfolk in 1973. It was the day before she was to be towed out into the Atlantic and sunk. I walked through the operations area and stood in a

passageway where my friend LCDR Dave Lewis had lain severely wounded on 8 June 1967. After all the effort to save the Liberty and bring her home for repairs – now she was about to make her last cruise. This Spy Ship’s Cold War was over.

In Memoriam – LT James Cecil Pierce, USN,

Buried, Section 13, Arlington National Cemetery

Read other articles by Commander John Murphy

Read other Cold War Warrior

Articles

|