|

Historical Society note: The Contralto is a book published in 1912 and based on actual

residents of Emmitsburg. In the original version, the author modified the names of the residents slightly, such as changing the name if Isaac Annan to

Isaac Hannan. In this electronic version, we have taken the liberty to change names back to the real names. In addition, we have added

photos of the time period depicting scenes and characters in the book (the original book had no photos) and hyperlinks to related stories in our on-line

archives. While the book is 'theoretically' fiction, it does nevertheless correctly depict the life and

attitudes of the residents of Emmitsburg during the time period in question. We take note of the depiction of the ill feelings held by some towards Mount St. Marys and

St.

Joseph's College stemming from their poor treatment of the residents of Emmitsburg. The percentage of the book dedicated to this subject is itself a statement of the depth of those ill feelings. Fortunately, those ill feelings have long since vanished and both institutions are looked

upon as a treasure to this community.

The first and only mention of the book appears in the November 20, 1912 edition of the Frederick News Post:

'The Contralto a new book which has just been published and in which the scene is laid at Emmitsburg. A love story

is given in which a number of well known characters about Emmitsburg are interwoven The names are disguised in part, but not so much that they cannot

be recognized by a person familiar with the names in that section. The book is by Roger M. Carew, who spent the summer of 1910 in

Emmitsburg. It is said Carew's real name is Charles M. Maloy."

The Historical Society is still researching editions of the Emmitsburg Chronicle, which has a

major supporting role in the book, to ascertain if in facts the columns noted in the book were in fact ever written. We've also determined that

the story was in fact written by Rev. Charles Maloy, C.M.. Who resided

at St. Josephs during 1906-07. To

follow our progress click here.

The Contralto

Rev. Charles Maloy, C. M.

St. Joseph's Parish, Emmitsburg, Md.

|

Peter Burket |

Chapter 1

The regular morning gathering of Emmitsburg notables was in session in Peter

Burket's store. It was just such as had

assembled every day for over fifty years, even in the time when Peter's father conducted the grocery business and catered to the wants of the village in

the valley. The personnel changed, new members replacing those who were gathered to their fathers, but subjects of discussion, ranging through local

gossip, politics and religion, remained ever the same, and were carried on with that love of argument for its own sake which characterizes those who

dwell far from city strife.

On the entrance of a stranger the assemblage became mute, mildly suggesting devout Orientals in worship about their

idol, the fane in this case being the white-bellied stove in winter and the capacious box of sawdust in summer. This attitude was assumed in order to

give the intruder striking evidence that he was an outsider, as well as to afford opportunity to observe the nature of his purchase for subsequent

remark.

In these meetings were threshed over the latest action of the President, the last enactment of Congress with

consideration of the position taken by the local Representative, and the ruling of the Squire in the most recent arrest that came before him. The

improvident farmer about to be sheriffed out, together with the luckier one upon whom prosperity had smiled to the extent of requiring a barn-raising,

received his due need of praise or blame.

|

Bennet Tyson |

Religion was sure to become a bone of contention at some moment of the discussion, and then the debate was

monopolized by Uncle Bennett Tyson, the town carpenter, and Deacon Whitmore who mixed the making of cigars with the profession of local exhorter. At

this stage the other members looked on in amusement, prodding the embers of theological discord with spasmodic remarks. Victory invariably rested her

crown on the carpenter's brow, the Deacon never learning discretion from oft-repeated defeat.

This particular morning debate waxed strong on the propriety of the Chief Executive eating with a leader of the colored

race. Living on the borders of the Southland, opinion was almost unanimous in condemnation, Whitmore alone supporting the President's action. He could

not refrain from taking a religious view of the question:

"The Bible says, all men are equal before the Lord," he drawled.

"The Bible don't say nothing of the kind," snapped Bennett. "The Declaration of Independence has something to that

effect, but that ain't the Bible by a darned sight. As far as I know the Good Book it says the sons of Ham are to be subject to the white race."

"So it does, Bennett," in a tone of conciliation, "but you fought to free the colored people."

"No, I didn't, I fought to preserve the Union, and that feller in Washin'ton is trying to break it up again. I say keep

the niggers where the Lord put them."

"That's all right," retorted the Deacon pulling the straggling goatee which ornamented his chin, "but Paul saith, the

Lord ain't no respecter of persons, before Him there ain't no bound nor free."

"The Lord is a long ways off, and Paul didn't run no underground railroad, but sent the slave back to his master."

There was a pause during which Whitmore sought vainly for a telling rejoinder, the onlookers dug elbows into each

other's ribs and the champion munched his tobacco in semi-triumph. Flattery of his opponent seeming the better part of valor, the Deacon at length said:

"Why Bennett, you know the Scriptures good enough to be a preacher."

"What's that?" he asked, for he was slightly deaf and used his affliction as a ruse to obtain time to think out a

reply.

"I say," repeated his antagonist in a higher key, "you know your Scriptures good enough to be a preacher."

"Only one thing lacking, Whitmore, only one thing lacking."

"What's that?"

"A few damned fools to listen to me."

The volley of laughter that greeted this victory of the carpenter died out in short lived chuckles on the entrance of

Bob Crittendon, the red-haired, freckled boy from St. Joseph's parsonage, who generally had something to tell which served as pabulum for the gossips. Bob's

face was alight with a broad smile on surveying the expectant assembly, he evidently realizing the important position he occupied in village affairs,

and enjoying the prominence derived there from. He waited until the inevitable question should be put to him; it came.

"Anything diddin', Bobby?" inquired Forman the dentist, who showed his superior education by his manner of pronouncing

the current idiom.

"Yep; the Professor has come to."

"How was it did?" asked Peter Burket hastily, from behind the counter where he was retailing soda crackers, having

broken one to secure the exact weight, and given the piece to the child customer.

"Tell us all about it," encouraged Whitmore.

"Well it was all on account of my baseball and mitt—"

"Can he play ball?" interrupted Forman.

"Can he? You'd just ought to see him make me duck about after inshoots, outs, and drops; man dear! he's got a arm like

a trip-hammer, and when he began to burn 'em in he made my hand sting like as if I had it in a beehive."

"I knowed he was a all right feller," declared the Deacon nodding his head.

"Why you was the one said he was dangerous to have around with so many young girls in town," said Uncle Bennett

scornfully.

"So he is a ball player," continued the Dentist, anxious to prevent hostilities which might delay the obtaining of

knowledge about the mysterious being who had been the object of talk for Emmitsburg during the past month. "Did he tell you anything about playing on

a team?"

"Nope, but I'll bet he played on some university."

"How do you know he ever saw a university?" sniffed Doctor Brawner, the town's physician.

"Ain't I heard him and the Rector talk at table?" retorted the youngster indignantly.

"What did he talk about while he was catching with you?" injected Forman again anxious to keep the peace.

"He asked me if we had a team in town, and when I told him there wasn't enough young fellers

Left here to make one up, he said if he was here nex' spring he would organize one out of schoolboys."

"Let him get it up now and wallop the pants off the Mount St. Marys bunch," suggested the Dentist.

"They wouldn't play with a team from this town," aid the Physician scornfully.

"I'd like to know why not? We're just as good as they are."

"Well, try it and find out."

The whistle of the morning train ended the contention for all were due at the post office, yet everyone felt that Bob

had imparted an important piece of news. Strangers were aves rarae in Emmitsburg, and this one had the superadded attractions of youth, good looks and

mystery.

The town is situated at the base of our most easterly mountain chain in a valley noted, according to the local paper

and the school catalogues, for the salubrity of its climate. One central street with houses of every conceivable architectural plan, baroque a critic

would call it, though the history and financial rating of a hundred years could be read therein, bisected by the road over which a division of the Union

army marched on its way to the high water mark of the rebellion, makes up the topographical aspect of the village.

"Emmitsburg's a pretty place, not far from the mountain,

Most of it's along one street, and in the Square's a fountain;"

sang a native truthfully, if not with poetic inspiration. The hills look down on the town with a suggestion of the

fixity of the everlasting, telling the inhabitants of the vanity of all change and progress, and the town nestles at their feet in the pose of a tired,

sleepy pupil who has heard the lesson a thousand times before.

Old fountain in center of square ~ 1900

(History of the Fountain of Emmitsburg)

|

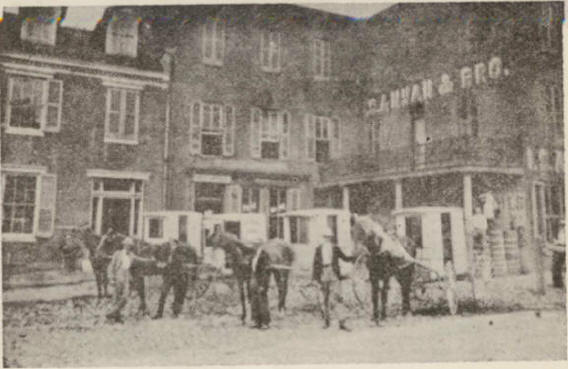

Hotel Spangler (SE Corner)

|

|

Isaac Annan's General Store &Post Office |

Flanking the square are the Spangler Hotel, the Annan's Bank and General Store, the Seabold Building, with the law

apartments of the owner, the post office and what was Peter Burket's Grocery.

A hundred yards west is the printing office, the home of the "Chronicle"

which had lately passed into the hands of a progressive and was attracting the notice of the scissors editors on the city dailies.

At the upper or west

end of Main Street just where the roads fork stands the Emitt House another of the five dispensaries of liquid optimism which cater abundantly to the

thirsty ones of the village and the surrounding country.

About a mile to the south one comes to the first of the institutions which shape the ends and rule the destinies of

Emmitsburg. It is the Academy for young ladies, St. Joseph's College, that has, for more than a century, developed in things educational, its share of the first women of the

land.

St. Joseph's Academy

Some two miles further and part way up the mountain is the College, Mt. St. Marys, from out whose portals during its

hundred years of existence, have passed men famous in Church and State. Both are centered in magnificent isolation, surrounded by hundreds of fertile

acres, upon which labor the townspeople, and over which rule the respective presidents and faculties with all the authority and sometimes haughtiness of

medieval barons.

The village folk are kept in subjection not with guns and donjons but by the much more respectable, though none the

less effective measures of economic pauperism and social ostracism. The professors rarely visit the town except to call at the parsonage, or to inquire

into some misdemeanor perpetrated by the hopefuls entrusted to their care.

There are a few families in the village dwelling at the east end of Main Street, not dependent on the institutions for

their means of subsistence; families whose circumstances raise them above the twelve dollars-per-month rate of wage which prevailed. These form a social

group apart, taking only a mild interest in the affairs of the town, though on familiar terms with everyone and furnishing a ready subject for envious

gossip when others fail.

Outside the crowds of alumni who come at commencement time and occasional drummers, the people meet few from the great

world that lies beyond the mountains. It is small wonder then that the arrival and residence amongst them of a handsome stranger should pique their

curiosity to the utmost.

In the early days of August the evening train brought him to the town. All the way up from Rocky Ridge, where the

change is made from the Western Maryland railroad, he rode in the last seat of the smoker, his head sunk on his breast, in his mouth an unlighted cigar.

No effort of Mr. Webb, the genial conductor, was sufficient to awaken a response, and that worthy confided with a wink to

Mr. Seabold, his opinion that

the stranger must be sick.

Mr. Webb was right in his surmise, the stranger was sick—sick with a disease all too common in this hustling land of

ours. He was a victim of overwork and one of its most serious accompanying evils. Had he been asked to describe his own condition, be would have summed

up his outlook on life by saying, "he did not care whether school kept or not."

Thinking of this as he rode over the anything but smooth right-of-way

which leads from Rocky Ridge to Emmitsburg, a mixed smile of fatalism and self-pity played on his features.

At the conductor's' announcement of the end of his journey, he pulled on a light overcoat, picked up his hand-bag and

stepping out on the platform, became the cynosure of the crowd that always meets the evening train.

He was a tall man just barely short of six feet, shouldered, athletically stooped, his fine face bearing signs of

recent if not present illness. At temples the thick brown hair was threaded with, premature, one would say on close inspection his face. Pince-nez

glasses hid his eyes, which deep blue and could flash fire when the spirit behind them was moved. The hand that held the was muscular, though as white

as any woman's.

|

Hotel Spangler Carriage |

|

Emmit House Carriage

|

On leaving the train his ears were assailed with of "Hack right out to the College! Hotel "Spangler bus!" Handing

the bag and check to of the drivers he climbed into the nearest conveyance; the trunks being lifted to the seat, he destination discovered, the horses started up this declivity,

followed by the boys who speculated audibly on the newcomer's identity.

At the rectory the Pastor seemed to be waiting, for as soon as the hack arrived the Stranger was wrapped in welcoming

arms, and the driver heard this much:

"Is it you, my boy? I am pleased to death to have you, what was it anyway?"

"I don't know; doctors said brain fever, overwork, every and any old thing in medical history; I would not like to tell

you what some people said."

"Don't mind, I know; it doesn't go with me. Take those trunks up to the third floor," this to the driver, "and come

down, Harry, and have some supper."

Pad way up the walk, as the hackman reported afterward on the Square, the Stranger halted and said with a laugh, "I

say, Governor, why don't your educational institutions influence the town?"

"In what way?"

"I saw a sign on one of your Noah's arks at the depot: 'Free Buss.' Do they supply a kiss with every ride?"

"Hush, my boy, you are not in the city now," and the driver heard no more.

This was about the only authentic information concerning the newcomer that had thus far reached the inhabitants, though

serious efforts were made to solve the mystery which enveloped him in the popular mind. From conversations, snatches of which Robert overheard while

waiting on table, the inference was drawn that he was a teacher somewhere, and those who met him on his walks, deeming it neighborly to salute,

addressed him as "Professor." The name stuck as long as his destiny was linked with the village. Robert likewise reported sundry tilts between the

Stranger and the "gents" from the College who happened to dine at the parsonage, in which, as the boy judged, the "gents" were sadly worsted.

His reserve was a sore trial to the young maidens, for men were decidedly scarce, and a flirtation was one of the few

divertissements in their monotonous lives. Their eyes were apparently wasted on the armor of reserve with which he had clothed himself; failure to find

out all about him finally giving rise to weird tales the repetition of which only whetted the appetite for the truth.

The first week of his sojourn he took long solitary walks on the mountain roads, ruminating on his exile, his

banishment from all that made life worth living, his failure in the ways in which he had chosen to go. Soon, however, he learned the wisdom of Paul

Bourget's declaration:

"There are certain corners of nature of a beauty so sweet that it is human, so delicate that it is affectionate,

seeming to have been made expressly for the reception of great sorrows, and the enveloping of them in an atmosphere of calm."

The mountains in their colossal stillness, bearing on their backs without a murmur century old oaks and chestnuts, were

reflected in him by a feeling of strength which found expression in a straightening of drooping shoulders, and a driving of resolute heels into the

earth. Drinking in unconsciously the vigor of nature that lay round about him, he came out of his "Tower of Ivory" in which the years of study had shut

him, and learned that the world possessed something worth knowing which was not acquired from books. Later a beautiful bay saddle horse and a large

collie dog arrived and the three became oft-seen figures on the mountain side.

At this several bold attempts were made to wrest his secret from him and horseback riding. revived amongst the young

women. No success crowned their efforts, so Miss Lansinger, the church organist, goaded to desperation, declared before the assembly in Burket's store,

that she would make his acquaintance within a week or confess herself a hopeless old maid. Mrs. Hopp, the village "Holy Terror," disgusted with the

defeat of the younger element, took the burden of discovery heroically upon her aged shoulders. Meeting him, she halted with:

"Good morning, Mister."

"Good morning to you, Madame," pleasantly. "Be those store teeth?" pointing to his smiling mouth.

"Store teeth," he mused, puzzled, then laughing aloud; "hardly, unless they were purchased in the Almighty's Painless

Parlor."

"Well, I didn't know, all the boys and girls hereabouts wear store teeth."

"I cannot remove these," suiting the action to the word and continuing his walk. Mrs. Hopp voted him a little uppish

but was sure he would thaw out.

There was one person in the village, to whom the presence of the Stranger was not a mere problem of idle curiosity, but

a matter of the utmost seriousness foreboding direst possibilities. Mrs. Mary Neck was the Protagonist of morality in Emmitsburg, self constituted it is

true, but zealous beyond measure. From the very first she frowned on the newcomer, exhorting all to beware of him. She had a brother who worked in New

York and often had he told her of the ravages wrought by city young men thrown amongst country girls. The fact that this one was vouched for by his

residence at the parsonage did not in the least affect her distrust. Every day she trundled her perambulator, carrying her baby daughter Elizabeth, past the rectory keeping solitary and

vigilant watch. One count in her indictment was that he had passed her baby a number of times without deigning to notice it, though she had observed him

frequently fondling a fat two-year-old on a neighboring porch.

Such was the attitude of Emmitsburg toward the Professor when Bob Crittendon made announcement to the assembly that he

had come to, hence it was small wonder the news passed quickly from mouth to mouth at the morning mail. It was received with varying comment, the

younger element favoring Forman's proposition that he be requested to organize a team, and play the juniors at the college, the elders smiling cynically

at the futility of the suggestion. While the discussion went on the Stranger rode up to receive his mail from the red-haired youngster, whom excitement

had rendered forgetful of duty. As he opened and scanned a letter Bob spoke:

"Say, Professor, we all been talkin' about a baseball team; couldn't you all get one up?"

"It's too late in the season, Bob; wait until next spring."

"That's a long way off, Professor; we all could get a game with the college before cold weather; Doc here is willin' to

be manager," pointing to the dentist.

"But would we have time to get sufficient practice?"

"Sure! we all know how to play; we only need a little coachin'!"

"Very well then," smiling at the boy's earnestness which was reflected in the faces of the younger bystanders, "meet me

at the rectory this afternoon at four and bring all the good-sized boys in town."

Bob pirouetted like a dervish as the Professor gathered up his reins and followed by the dog galloped towards the

mountains.

That evening Peter Burket sent a long order to a sporting goods house in the city, and delivered a lengthy

dissertation on the financial rating of the Stranger, assuring his auditors there was nothing cheap about him. "Why, sirs, do you know what he went and

done? Made me add fifteen per cent to the catalogue price as my commission, and when I objected because there was something goin' to be did for the

amusement of the village, he only laughed and insisted. Yes, indeedy!"

"Well, well!" exclaimed Uncle Bennett, after a pause during which the news of such astounding generosity sank into the

minds of the assembly, "and to think that a baseball fetched him to!"

Chapter 2

Click here to see more historical photos of Emmitsburg

Have your own memories of Emmitsburg of old?

If so, send them to us at history@emmitsburg.net

|