|

The Contralto

Rev. Charles Maloy, C. M.

St. Joseph's Parish, Emmitsburg, Md.

Chapter 2 | Chapter 1

|

Playing Baseball on Fireman's Field ~ 1909

|

During the next two weeks "Fireman's Field" was the busiest portion of Emmitsburg, the center of daily

gravitation for young and old, not excluding the females.

The Professor had indeed "come to." He entered heart and soul into the practice, teaching the youngsters to bunt, work

double-steals, and squeeze plays, until the onlookers declared there was more in the national game than the most enlightened of them had ever dreamed.

Uncle Bennett was enthusiastic, examining the mask, protector, and above all the wood and turning of the bats. The

Deacon unable to resist the magnet, confined his participation to the occupying of a seat in a corner of the worm fence that enclosed the field. Peter,

leaving the store in charge of his wife, sauntered down to regale the boys with stories of his batting prowess in the good old days when he played

left-field on the Bridgeport nine.

His boasting one day led to the laying of a wager by Bob, who had qualified as catcher of the team, that the Professor

could strike the Grocer out. The trial was on after much good natured chaffing amongst the spectators, and Crittendon dressed in mask, protector and

mitt, stood almost over the plate.

"Look out I don't hit you, kid!" exclaimed Peter as he swung the bat.

"Hit away," came back the red-haired warrior. "Don't stand so close," yelled several of the on-lookers.

"I know what I'm adoin'," said Bob as he stooped over holding two fingers of his right hand on the palm of the big

glove.

The Professor wound up, the ball shot straight for Peter's head, that worthy stepping back as it curved gracefully out

landing squarely in Bob's mitt. "Strike one," shouted Forman, who had volunteered as umpire. The batter looked sheepish while the crowd laughed.

Crittendon was again leaning over, this time his index finger jammed into the mitt; again the sphere was thrown, Peter aiming a vicious blow, only to

hear the wind as the ball passed with speed between his hands and face. "Strike two," roared the Dentist doubling up with laughter. Peter gritted his

teeth while Bob sank down on his knees and waited. Now the Professor assumed the contortions of an acrobat, the ball leaving his hand floated like a toy

balloon on a summer breeze about a foot above the batter's head. He made one more drive as it slowly sank, but it snuggled in Crittendon's mitt, just

behind the plate. There was a burst of applause from the crowd, while the Grocer walked to the pitcher, shook hands, then took his place amongst the

onlookers, offering to bet five dollars that no man in the county could hit even a foul, with the Professor "serving 'em."

The Rector heartily approved of the younger man's athletic interests, even arguing when the latter sowed signs of

retreating within his shell, which happened at times in their conversations. He was not sanguine in the matter of a game with the college boys, However.

"You have a lot to learn about affairs here, " he said one day at lunch.

"To what do you refer, Governor?"

"To the attitude of the institutions towards the people."

"Perhaps I have been learning something. I know that they hold the people much in the same light as our successful

'Captains of Industry' do their employees, a sort of rudum pecus socially, and a necessary evil economically."

"A common herd," translated the Parson, "with-out the protecting guidance of organization or leadership. Did anyone

attempt to teach these people that they have rights other than to work for the merest pittance, to join the bucket-brigade to the kitchen doors of their

taskmasters, he would bring upon himself the everlasting enmity of both institutions. Father Henry, my predecessor, tried it, and is now on the foreign

mission. I fear if you play the game, and particularly if you chance to win you will make things miserable for yourself and the poor fellows who depend

on them."

After the delivery of this explanation the two ate in silence for some minutes; it was evident, however, that the

younger man was thinking. At length, he said in very even tones:

"Several summers ago I went west for my vacation, and lived the life of a cattleman, as much as a tenderfoot could hope

to do so. I rode trail from my arrival until the fall round-up. I witnessed one stampede, and never desire to see another. For months that herd had

grazed and slept like the lambs of the Scripture. One clear starlit night, something started them. Well, 'there's a Divinity which shapes our ends' or I

should not be here to tell it. The oldest rangers could assign no reason, all agreeing the cause was too insignificant to seek; the effect was

tremendous. Sometimes in looking at the hang-dog, submissive expression on the faces of these people I have been reminded of that scene. Would it not be

remarkable if a little thing like a baseball game should arouse the slumbering spirit of Emmitsburg?"

"It would take a moral earthquake to awaken them from the lethargy of the ages which wraps them round," commented the

Rector shaking his head sadly.

"And yet such things have happened."

Meantime Forman, as manager, had opened negotiations with the athletic committee of the College, having progressed to

the point that the game if played, must be held on Sunday, as the football team had the call on the grounds for all other occasions. The Dentist was of

the kind to take the whole village into his confidence and excitement ran high in anticipation of the game. The young girls were busy making pennants of

red and blue, the colors which the Professor had adopted out of a sentimental memory for his Alma Mater, while the boys were provided with a song by the

town poet. Dr. Brawner was skeptical, declaring the President would never allow the game to be played, and certain church people were loud in their

condemnation of the contemplated desecration of the Sabbath.

Affairs were at this pass when one Monday morning the moving spirit rode down Main Street. Turning into the Square, he

beheld a group standing outside the post-office to which the manager was reading a letter. Coming to a halt he overheard language of protest:

"They're askeared of us," shouted Bob Crittendon.

"Right you are, Bobby, agreed Dr. Forman with evident chagrin.

All looked in mute appeal at the Professor as he read the letter the Dentist handed up. It was in almost illegible

scrawl which when deciphered read to this effect: it had come to the ears of the President that certain persons were endeavoring to arrange a baseball

game to be played at the college on Sunday. The assurance of these was astounding, as no one had consulted him in the matter, and the idea of holding a

game on the Sabbath was insulting to the religious principles of the college people. It ended with an order that Dr. Forman and his abettors refrain from

taking any such liberty in the future.

The letter was folded deliberately and handed back while the crowd waited for comment; none was made and after a pause,

Bob voiced the disappointment of the group:

"It's all up with the team for this year," and the genuine sadness in his tone caused the man on the horse to look upon

him with soft eyes of sympathy.

|

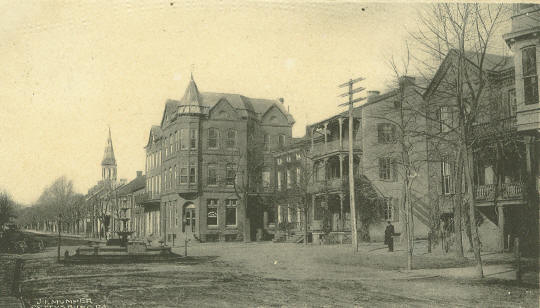

Annan's Bank (NW Corner)

|

Bob's lament was the signal for loud protests which broke out in the crowd, taking the form of assertions that the

college was afraid of defeat, that they always practiced on Sundays and compelled their men to work on that day in harvest time.

Mr. Annan, the cashier at the

Annan-Horner Bank, however, took up an attitude of condemnation of Sunday baseball in general, with particular caustic aspersions on folks from the city bringing

their disregard for the Sabbath into this well regulated town.

All the time he was speaking, the Professor sat his horse in a mood of abstraction. The Cashier's last words seemed to

startle him, however, for he immediately got down while the crowd made way respectfully. Crossing to where the objector stood, he said in icy tones:

"I have not the honor of your acquaintance, but it appeared that your last remarks were addressed to me."

"You may take them if they fit you."

"It is quite evident you object to baseball on Sunday."

"I object to you bringing your lack of respect for the Sabbath into our town."

"I want to ask you, Sir," and the words cut like a knife, "whether it is more wicked to play baseball out in God's

sunshine, than to sit as you did yesterday up in a back room of the Spangler, playing poker and winning the money that should go to feed, clothe, and

educate Jim Elders' children?"

Annan was petrified, the crowd gasped, while the Professor prepared to remount. With one foot in the stirrup he turned,

"There is only one way to handle a cad like you; any time you are ready, let me know, and I shall meet you quietly and break every bone in your damned

carcass." With this he swung into the saddle and he, the dog, and the horse, were soon lost in the September haze.

The members of the assembly repaired to Burkett's from unanimous impulse, and once inside Dr. Forman broke out:

"Oh me! oh my! did you ever hear anyone put meaning into a cuss word like him? I've been using that kind of punctuation

for years, but I never understood its value until I heard him say your damned carcass. "

"I don't approve of cussin' any more than I do of Sunday baseball," declared Whitmore, "but I sure would hate to have a

altercation with that young feller. "

"We're going to hear from him before long," said Uncle Bennett forgetting to take up his antagonist. "The college

people should have writ a more civil letter; they may find he's a bad man to monkey with just like Ike Annan did."

"What do the college people need to fear from him?" asked Dr. Brawner skeptically.

"I didn't say they got anything to fear from him," snapped Bennett, "all I say is they'll hear from him yet."

"Say, Doc," said Forman, "you and some more people around here have an idea that if the college people were to be

offended this darned town would disappear from God's footstool."

"Well, I wouldn't advise you to do the offending if you intend to stay in this neighborhood."

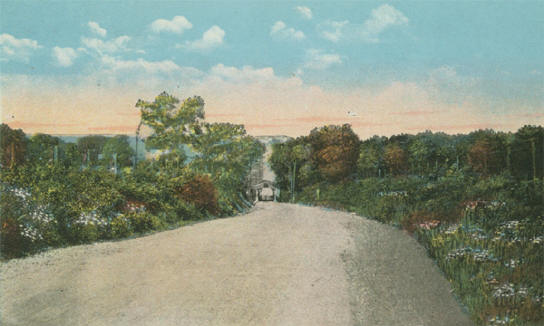

The Professor's horse was breasting the mountain at a heartbreaking pace, the dog keeping ahead with lolling tongue and

heaving sides. Both were puzzled for they had never been put to it so hard before. Every little while the collie looked back, an anxious glance in his

intelligent eyes. The master took no note of the distress of his pets, his mind was a maelstrom. At times he laughed harshly as he thought of what the

people at home would think of him acting as a common street brawler. Again he considered the foolishness of his taking an interest in this stupid

village which, as he told himself, would defame him at the first opportunity. Better that he withdraw within himself and spend his time in selfish

concentration. Extracts from Renan, Maubert, Nietzsche, the other supermen, chased each other in wild medley through his brain.

At length he seemed to realize that his companions of the trip required consideration, and pulling up the horse,

shouting to the dog, he looked at his surroundings. They had come a long way, just around a bend was the Mountain House, where he usually stopped for

rest when his rides took him in that direction. Dismounting he led the horse and followed by the dog walked into the yard of the hotel.

Seated on the porch of the hostelry he gazed on one of the most calmly beautiful scenes that is anywhere unfolded

before the human eye. For miles at a thousand feet below stretched a peaceful valley, in certain fields of which the yellowing corn stood breathless.

The whole appeared as one huge chessboard on which the white farm-houses, the red barns, the stacks of straw, held the places of pawns, knights and

castles. Over all hung the blue haze suggestive of infinite calm. Looking off to his right he thought of that July day when the flower of southern

chivalry marched through the gap in the mountains to the great struggle which sealed the destiny of a nation. An elemental battle was beginning in his

own soul, an obsequious waiter who had learned his commercial value was the enemy incarnate.

"'Mornin' suh, anything this mornin'?"

"I shall take lunch here."

"Yas, suh; hors bein' tended to, suh?"

"Yes, and by the way, you might fetch me a mint julep," with some hesitation.

While giving the order a voice deep in his conscience warned him not to do it, but he argued against it. One would not

hurt him, it would make him feel better after the upsetting scene of the morning. The opinion of the business-like specialist came to him like a blow in

the face: "If you don't wish to go blind you must cut out the alcohol." But there was not sufficient in one julep to rob him of his eyesight, and

moreover those specialists were cranks on some points.

The waiter returned with the appealing concoction, placing it on a small table at his side and discreetly withdrawing.

Raising the straws to his lips he inhaled the odor of the fragrant mint. Memory was at work again, another scene came strikingly to his mind; a railroad

depot, an elderly woman and a young daughter waiting anxiously while he helped an old pedagogue up the steps of a car. He recalled with hot blushes the

scorn in the faces of the ladies, for be had taken the old fellow out between trains to have a julep and had allowed him to become drunk. During this

vision the glass was slowly returned to the table, while a sickly smile spread over the features of the Professor. After a moment more of thought, he

took a sprig of mint from the glass and held, it to the collie who lay at his feet.

The wise animal smelled the herb, then turned away in disgust. "You wouldn't touch it, boy, neither shall I;" so saying

he emptied the glass over the railing and walked into the dining room.

Luncheon over he once more sat on the porch and looked down on the quiet valley. Outwardly he was in perfect harmony

with his environment, but a blazing fire within. The blood coursing through his veins seemed aflame; while at odd moments he felt his pulse, exclaiming

aloud: "My God! it's an awful fight. How long is it going to last? That one struggle today is but a sample. How many more, O Lord, how many more!"

Nearing the town on the return his ears were pierced by the shrill calliope of an auto, an unaccustomed sound in that

region, and rising above the last descending hill a large car sped past him, a noisy crowd of college boys within. He smiled as the youthful occupants

yelled with all the contempt of the plutocrat for the less fortunate, the horse shying at the waving hats and arms. The dog trotted on ahead, coming to

an abrupt stop at the foot of the hill where he gazed at the form of a young woman who sat on the roadside, her face buried in her hands. The posture

attracted the attention of the Professor who, halting, murmured to himself, "a fair demoiselle in distress."

"Beg pardon," he said aloud, "you seem to be in trouble."

"Yes, air, " aising her tear dimmed eyes, "my horse took fright at that auto which just passed and ran off."

"Did he throw you?"

"No," with spirit, "I got off to hold him when I saw the machine approaching, and as I attempted to remount he took it

into his head to bolt. "

"Did he drag you?" dismounting.

"No, simply gave my ankle a twist," with a smile that ended in a twitch.

"You must take my horse, he is very gentle; I shall remove the saddle."

"That isn't necessary," with a light blush as she directed his attention to the divided riding habit.

"Of course not," he agreed with an arriere pensee to the effect that everyone in Emmitsburg was not behind the times.

"But really I couldn't think of making you walk," she protested weakly.

"Nonsense!" laughing and bringing the horse nearer, "come, up you go."

She attempted to rise but, the effort causing her pain, would have fallen had not his arm caught her round the waist.

"Just a moment," he pleaded; then lifted her bodily into the saddle. As he adjusted the stirrups he looked up and there

was a defiant gaze in her eyes. When all was ready he told her to proceed, instructing her as to the methods of handling the horse, and stepped aside.

"I would prefer you to walk near him," she said, "my nerves are a little shaken."

"Just as you wish," taking his place at her right stirrup, telling the horse to be good, and the girl that this was the

first time the "Admiral" ever had the honor of carrying a woman. The ride was a very quiet one, she sitting the horse and looking straight ahead, he, at

first having endeavored to make conversation, joking about the mishap, inquiring every few steps about her ankle, found this one-sided, and relapsed

into silence. Before entering Main Street, however, the girl pulled the horse up saying:

"This will be the talk of the town."

"What, my picking you up when you had sprained your ankle? If they be so sorely in need of matter for gossip, I

consider myself a benefactor in supplying it."

"Oh! you don't understand," she returned with anxiety.

"Perhaps I don't; could you enlighten me? I don't see the least impropriety in not leaving you to bleach your bones on

the mountain road, " smiling at his mock heroics.

"Well, I don't care what they say," starting the horse defiantly.

"Thank you; I am glad you are not going to rob the Good Samaritan of his halo."

Turning into the village they could hear windows being raised, suppressed calls of warning from house to house.

Emmitsburg, awakened to a new sensation, was enjoying it to the full. The Professor bowed from side to side as he recognized acquaintances, but the girl

sat the horse with the posture of Jeanne D'Arc facing her God-inspired mission. Near the Square stood a group of people, a man holding a restive horse.

A tall, light-haired, young woman stepped from the sidewalk inquiring:

"Are you hurt, dear?"

"Just a twisted ankle."

"I caught him before he got to the house," said the man with the horse, "I didn't want him to frighten your mother to

death."

"Thank you, Tom; now I shall change and ride him home."

"Oh, Marion, dear! please don't get on that beast again, he will kill you," pleaded the light-haired girl.

"Better not Miss Marion," advised Tom, "he's pretty nervous."

"Let the Professor ride him," suggested one of the group, "you stay where you are."

Without comment the Professor took the bridle from Tom Greavy and vaulted into the saddle. The horse cavorted about the

Square for a while, but realizing there was more than a woman's hand in control, submitted gracefully, allowing himself to be guided alongside the

other, and the two moved down the street at a decorous pace.

At a large house near the lower end the girl announced simply: "This is where I live, "turned in the gate, followed by her companion.

A tall woman in middle life, showing marked evidences of refinement, opened the door as the young woman slid from the

Admiral's back: "What is the matter, Marion, are you hurt, child?"

"No, mumma dear, the Professor and I have been swapping horses," but noticing the look of reproval on her mother's

face, quickly added, "I twisted my ankle and this gentleman rescued me."

"I am exceedingly grateful to you sir," bowing, "won't you come in?"

Looking at the girl who had sunk into a chair, and thinking he saw an appeal in her eyes, he swung from the saddle just

as an old man came from the stable to lead her horse away. Tying his own to a post, he mounted the steps;

"Had I not better get a doctor?" he asked. "Yes," said the mother hastily, "what am I thinking of?"

"No, mumma dear, the sprain is nothing serious, I shall be well in a day or two, " but the expression of pain on her

face negatived her optimism.

"I shall telephone for Doctor Brawner at once," declared the mother, hurrying into the house.

"I dislike that old fellow, be is a mollycoddle."

"You require his orthopedic skill just now, so you must tolerate his shortcomings. Will you take my arm and allow me

to help you into the house?"

The girl tried to rise, but sank back with a tearful laugh. Without a word he picked her up, carried her into the

house, placing her in a chair and putting another as a rest for her injured limb, then without a by-your-leave began to unstrap the riding-boot. The

shoe removed, he felt the ankle professionally, remarking that it was swollen greatly. Looking at the young lady on whose face there was a shade of

embarrassment, he reddened in turn.

"Pardon my impulsiveness," he begged, "I have had some experience with injured members, and my anxiety got the better

of my respect for the proprieties."

"I wasn't thinking of that," she said, again blushing as her mother entered the room.

The doctor would be here in a minute, so the Professor took his leave after asking permission to call again. Riding up

the street he was the object of black looks from Mrs. Neck, who trundled her perambulator along the sidewalk.

Chapter 3

Have your own memories of Emmitsburg of old?

If so, send them to us at history@emmitsburg.net

|