|

The Contralto

Rev. Charles Maloy, C. M.

St. Joseph's Parish, Emmitsburg, Md.

Chapter 9 | Chapter 8 | Chapter 1

Five forty-five the next evening, the Professor was admitted to Mrs. Hopp's house by the lady herself who had donned

her best black silk for the festive occasion. Over the skirt of this she wore a dainty white apron with a pocket in it, which gave to her appearance a

somewhat youthful touch, while her grey locks were held back by old fashioned tortoise shell combs. She welcomed him, marvelling at his handsome figure

in frock coat, white waistcoat, and cravat in which sparkled a large solitaire. No one in Emmitsburg ever could afford to wear such clothes, except

Mr. Galt and she had never entertained him at tea. The most wonderful thing of all was, he in no way made her feel abashed, despite his grand

clothes. She found it as easy to talk to him as when she met him on the street dressed in his riding-jacket, breeches and boots. In the parlor she

noticed him looking at a large crayon of a young girl.

"That's my grand-daughter, Esther, she's on the stage. Don't you think she's beautiful?"

"Indeed I do, Mrs. Hopp," though the portrait pictured a type which never made an especial appeal to his aesthetic

sense.

"She's in vaudyville, though to tell the truth I don't know what that means. It's all right, isn't it?"

"Most assuredly, what is her line, her act? I mean what does she do in vaudeville?"

"Really, I don't know, but when she's in the city she coaxes me to come and see her. But there, now, you must excuse me

as I am busy in the kitchen." She left.

The Professor could not fail to remark that she did not retreat to the back of the house, but mounted the stairs.

Sitting in an easy chair he heard voices in whispered conversation. Mrs. Hopp was describing his appearance:

"God Almighty, girls! wait till you see him. Of all the handsome men! He's dressed to knock your eyes outólong coat,

white vest, striped pants, patent leather shoes, and a real diamond in his necktie."

"Not in full-dress, Mrs. Hopp?" asked Vinny, in dismay.

"Not one of those open-faced affairs, just a long coat, you know, like Mr. Galt wears, when he has his stove-pipe

hat on."

"I am afraid we are not dressed for the occasion," said Marion, surveying her own trim figure in mock alarm.

"Come downstairs, you beauties; do you think he's going to bother about your dresses when he's got your faces to look

at?"

They descended the steps in the wake of the old lady and into the parlor where the Professor received them with genuine

pleasure, expressing his gratitude to the hostess for the fulfilment of the surprise she had promised him. There was a touch of formality in Miss

Seabold's greeting, but Miss Tyson met him on nearer ground. Mrs. Hopp invited them to the dining-room to partake of her fried chicken, potato salad,

home-made preserves, tea and cake.

She presided with the native grace of a society matron and the young spirits at her table, catching her contagious

glee, gave themselves up to the present with the greatest abandon. The women learned more of the Professor's antecedent life than anyone heretofore in

Emmitsburg. He told of his experiences in the German universities, through which he had passed without the romance of a duel, of his ranch life to which

his powers of word painting added a charm not always inherent in the actual. His descriptions brought many exclamations from the excitable hostess at

which the girls shuddered in anticipation of his shock. Time slipped away under the spell of his talking. It was eight o'clock before the tea came to a

close. At the finish, Marion asked for an apron, insisting on helping with the dishes while Vinny was to entertain the Professor. It was evident that

Miss Dyson was accustomed to have her way from the ready acquiesence of her companion and the half-hearted protests of the Holy Terror.

Seated in an old fashioned fauteuil, having obtained the girl's permission, the Professor lighted a cigarette, she

balancing herself nonchalantly on the stool which stood before the ancient square piano. She inquired sympathetically about his health and the length of

his indisposition and whether his sojourn in Emmitsburg were benefitting him. As he expressed the hope that a year would find him in perfect condition,

she said wistfully:

"Even a year is not long, if you be assured of ultimate recovery."

"I believe, Miss Seabold, you are not over strong yourself, at least the Rector tells me you are not in the best of

health."

"Oh! the dear old gentleman and mother are worried because I cough a little. I think he suggested that you give me a

regimen, which would make me strong. I was compelled to leave school before graduating."

"He thinks me a paragon of science," smiling, "but really I shall be pleased to assist you in any way; you should live

in the open as much as possible."

"I do take long walks but they become monotonous, if one is alone. Marion comes with me frequently. I do not, however,

like to bore the dear girl with a continuous performance of invalid nursing."

"Surely, Miss Tyson's healthy and wholesome disposition must act as a tonic, why not form a party and go mountain

climbing these beautiful autumn days?"

"It would be delightful, could we get one up."

"I would deem it a favor to be a member. I also think swinging Indian clubs for stated periods each day is advisable in

a case the nature of yours; you learned to do that at school?"

"We had some exercises with them in the gymnasium, but not being interested I cut them as often as possible."

"I believe I could recall the essentials of the manual, had I a pair at present. We shall see what can be done."

Somehow there was a soothing, petting tone in his voice as he talked to the fair young girl, a tone more or less

fatherly.

Her culinary department being put, as she said herself, in apple pie order, the hostess and Marion joined the two in

the parlor. On their entrance he arose, escorting the old lady to the chair he had been occupying, treating her with the courtly grace of a cavalier of

old, she blushing and simpering like a school girl under his gravely sincere attention. He asked permission before lighting another cigarette.

"Law! yes, boy, go ahead, I do love the smell of those things, but God Almighty! how I hate an old pipe."

There was another catching of breaths at her lack of reverence, but Harry apparently took no notice. She was fidgetty

until Marion laughingly said:

"The Professor will grant you permission." "What is it she wishes?"

"Nothing at all," declared the old lady.

"She is accustomed to use snuff."

"You bold thing!"

"Help yourself, Mrs. Hopp," he begged, "I know you enjoy it as much as I do smoking."

Thus importuned she extracted a box from the pocket of her apron, indulging in a generous pinch, the while Marion, who

had taken the stool, played softly.

"Sing something, child," ordered Mrs. Hopp, "sing that nigger song of yours, did you ever hear it, Professor?"

Marion's rich contralto filled the room and floated out into the night in the soul-stirring strains of the lullaby,

this time the mother passion being enunciated in tones that the most uncultivated ear could appreciate. They entered the inmost fibers of the

Professor's being, searching out depths of sentiment, which he himself had never sounded, and died on his senses long before they ceased to re-echo in

his soul. Vinny applauded generously, the Professor forgetting to second her, the while Mrs. Hopp, having taken her handkerchief from her sleeve, wiped

her eyes suspiciously.

"That's grand," she avowed, "when Marion sings it she just makes me good for nothing."

"It is the very quintessence of feeling," added Vinny, "and Marion's rendering of it is perfect; could you not have Mr.

Halm interpolate it into the operetta?"

"Nonsense Vinny! come here and sing this duet." Their voices blended in a harmony, the like of which he had never appreciated before. He was in a receptive mood, thinking of and contrasting this with boring nights

at the opera, when he longed for the final curtain. This he felt should never cease. He was forced to sing and rendered some old college favorites in

the choruses of which the girls readily joined. At the hostess' special request the three sang "Aunt Dinah's Quilting Party," and it being half past

ten, prepared to depart. As they left, Mrs. Hoppe said:

"God love and bless you all, I'm ten years younger tonight and I'm going to have you often. Vinny, dear, draw that

cloak around you. Goodnight, Professor, God bless you, boy, come again, come again."

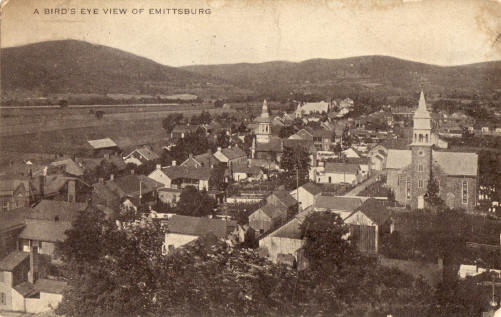

A birds eye view of Emmitsburg ~ 1910

Emmitsburg was wrapped in slumber, off on the mountain a dog barked, while nearby a rooster having had his first sleep

announced the fact to all within earshot. The party walked in silence, victims to the lull which succeeds to pleasant hours. Their footfalls echoed on

the rough sidewalks, made of lava cast up by some prehistoric volcano, sleepers could be heard turning in their beds at the unaccustomed noise. In the

Square, Vinny said: "My dear mamma is waiting up for me."

"I hope we have not kept you too late and caused her anxiety."

"No, mamma is always worried when I am out."

Mrs. Annie Seabold opened the door and clasped her daughter in a motherly embrace,

Freeing herself, the girl said:

"Mamma, you must meet the Professor."

"I am pleased, sir, and ever so grateful that you are kind to Vinny."

The simple expression of gratitude startled him and the threadbare words of convention were hopelessly stammered. Vinny

extended her hand with a cheery adieu and he and Marion were well down the street before he recovered his equipoise. He was about to speak when the

quiet of the night was broken by hideous yells, a mingling of curses and prayers that caused his blood to freeze. He seized the girl's arm in the first

moment of surprise but was relieved to find her laughing almost hysterically. Regaining self control, she explained that the rout was merely Doctor

Brawner in the throes of a nightmare, a periodical happening to which late movers in the village soon became accustomed.

They discussed Miss Seabold's health, the absence of an hereditary element being noted, her father and mother's

ruggedness and that of a younger sister at school in Washington remarked. Before parting they had made plans for mountain climbing, club swinging, and

other health producing exercises. Where sympathy rules, minds are preternaturally quick.

Before retiring, Harry picked up a book in order to quiet his nerves for in some inexplicable way, he felt agitated.

The words passed before his eyes but were not for a long time able to penetrate his brain, which was thoroughly occupied with the scenes of the evening.

At length, awakening to the import of the printed page, he read, "It is only the man whose intellect is clouded by his sexual impulses that can give the

name of fair sex to that under-sized, narrow-shouldered, broad-hipped, and short-legged race, for the whole beauty of the sex is bound up with this

impulse. Instead of calling them beautiful there would be more warrant for describing women as the unaesthetic sex. Neither for music, nor for poetry,

nor for fine art, have they really and truly any sense or susceptibility. It is a mere mockery if they make a pretense of it in order to assist their

endeavor to please." Pausing a moment in thought, he flung the book on the floor, gave voice to the eloquent exclamation "Rats!" said his prayers and

went to bed. The book was Schopenhauer's Essays.

At breakfast next morning the Rector inquired how he enjoyed the tea-party.

"Immensely. Mrs. Hopp is quite a character." "Did she blaspheme any?"

"She emitted her favorite ejaculation several times, though I am sure she was blissfully unconscious of the fact."

"It is a source of great concern to her young friends, who endeavor to show her the evil of her ways, but she

invariably argues back she does not swear."

"Two of them were there last night, Miss Seabold and Miss Tyson."

"Indeed! I am glad Vinny was there."

There was silence for a while during which both did justice to the substantial meal carefully prepared by Mary, the

housekeeper. The Professor noticed that food tasted differently to his palate of late, and that there was a real pleasure in eating, though it was not

preceded by the standard appetizeróa cocktail. Looking at the Rector, he quoted, "Condimentum optimum, fames, as we used to write in our Arnold's Latin

Exercise Book."

"I have not needed an appetizer since I was eight years old. I was a child in New Orleans during 'Spoony Ben's rule,'

and learned what hunger meant. The war is long over, we are an united country and all the newspaper stock phrases, but, my boy, I cannot behold the blue

uniform of a Union soldier without experiencing a cold shiver. I was walking along the street one day with my dear mother; I was leading my pet dog, a

mongrel as I remember, when a sharpshooter fired, cutting the strap, then shot the dog at my feet. It's over, thank God, but some memories are horrible.

By the way, there is another piece of reform work for you."

"Yes, Governor?"

"There's a dancing school about to be started in the opera-house, that shack behind the Spangler. You know I don't

object to dancing, but the crowd, which will gather there, will not be conducive to the moral welfare of the village. I want you to nip it in the bud."

"Don't you think such action would better come from you?"

"I am a failure, I would only waken antagonism, you are the man for all such work."

"Just as you say, Governor. Who is the head and front of the movement?"

"That plumber, who works for Mrs. Saddleberg, he is an amateur wrestler or prize-fighter, who came here from the city."

"I know him, Greavy, he's a good fellow, I don't think I shall have any trouble inducing him to give up the project."

"Don't be too sure, he is a hard-headed chap."

"I never yet saw one of those supposed thugs, who wasn't amenable to kindness. I shall give him the work of installing

the footlights and bring him around."

"I hope so," rising to leave the room. Harry was following, but before reaching the door was halted by a warning "Hist"

from Bob, whose head protruded from the kitchen.

"Professor, do you all want us to keep Jimmy Carrigan on the job?"

"Isn't he at work this morning?"

"Yes, sir, but you all don't know when he's goin' to make a break," a warning look on the freckled face.

"What is your method of keeping him to business?"

"I got fellows on the watch; if he makes a break, we all will grab him and fetch him back. We all don't intend to have

him spile the whole show."

"Does Jimmy know of this?"

"No, sir."

"Then go on with your plan."

"And, Professor, ain't you all goin' to need ushers and door tenders?"

"Certainly, why?"

"Got anybody picked?"

"Of course," seized with an inspiration, "the members of the baseball team are to attend to all that."

"Gee! whoop!" and Mary was once more convinced that Bobby was going stark mad.

Chapter 10

Click here to see more historical photos of Emmitsburg

Have your own memories of Emmitsburg of old?

If so, send them to us at history@emmitsburg.net

|